Event Program: 2025 Indy SpeedTour

THE FOUNDERS: INDIANAPOLIS MOTOR SPEEDWAY

By Rich Taylor

The rise of the automobile around 1900 was foreshadowed by the worldwide “bicycle boom” of the Gay Nineties, when chain-driven “safety bicycles” opened up new horizons for millions of people who could now travel faster and further than they could walk. Many of the men who later created the automobile industry started their careers and made their fortunes building these new “high-tech” bikes.

Once bicycle entrepreneurs switched to building cars, they needed a place to test and race them, too. Indeed, Indianapolis Motor Speedway—still the most important automobile race track in North America—was a collaboration between four members of the Zig-Zag Bicycling Club of Indianapolis.

Let’s begin with Arthur Calvin Newby. Born in Indiana at the very end of the Civil War, he was raised in California before returning to Indianapolis around 1885 and joining machine tool maker Nordyke Marmon. Five years later, Newby and two partners formed Indianapolis Chain & Stamping to make Diamond brand bicycle chains. They even supplied special heavy-duty drive chains for the propellers of the 1903 Wright Flyer and other aircraft built by their bicycle shop customers Wilbur and Orville Wright!

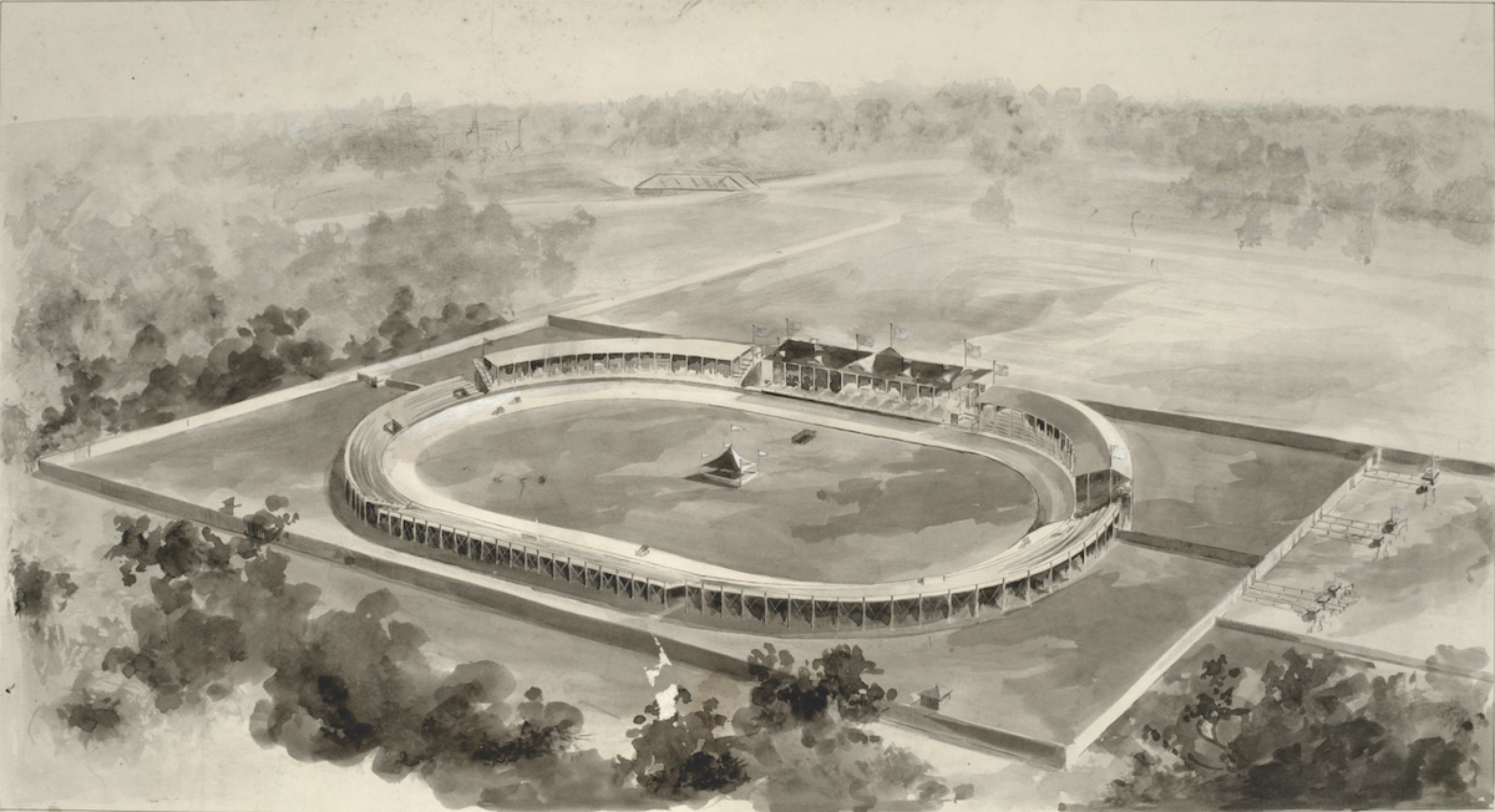

In 1898, Newby hired an architect to build a quarter-mile bicycle racing track planked with wooden boards. It was called Newby Oval, though it was really two banked half-circles connected by straights. Two years later, Newby invested in bicycle company Hay & Willits, plus started his own National Motor Vehicle Company to build automobiles. In 1908, he incorporated Empire Motor Car in partnership with another member of the Zig-Zag Bicycling Club, Carl Fisher.

Carl Graham Fisher also grew up poor in Southern Indiana. A decade younger than Newby, Fisher began racing bicycles as a teenager, then opened a local bicycle shop in rural Greensburg, 50 miles from Indianapolis. In 1904, he and fellow Zig-Zagger James A. Allison acquired a patent to manufacture acetylene headlights. They called their Indianapolis company Prest-O-Lite, and it quickly made them very, very rich. Prest-O-Lite supplied the headlights for almost every vehicle made in America before World War I.

James Asbury Allison was born in Michigan but moved to Indianapolis as a child. After his father’s death in 1890, he took over the Allison Coupon Company at age 18. He invented a new type of pen and started a second company, Allison Perfection Fountain Pens, to make them.

He met Fisher and Newby through the Zig-Zag Club, then partnered with Fisher to start not only Prest-O-Lite, but Fisher Automobile Company of Indianapolis. Selling Oldsmobile, REO, Packard, Stoddard-Dayton and Stutz, this is considered the first automobile dealership in the United States. Fisher and Allison even pioneered flamboyant car dealer advertising stunts, dangling a giant Stoddard-Daytona beneath a hot air balloon and flying it across Indianapolis!

Super-salesman Frank H. Wheeler was born in Iowa and arrived at Indianapolis in 1904 with enough cash to back automaker Harry Stutz and bankroll carburetor inventor George Schebler. Wheeler-Schebler quickly grew into a major supplier of automotive parts. Like his pals Newby, Allison and Fisher, starting from almost nothing, Wheeler made himself a fortune seemingly overnight.

When the 2.7-mile banked oval opened at Brooklands in 1907, Carl Fisher visited England to see it first-hand, then came home and announced “Indianapolis is going to be the world center of horseless carriage manufacturing, so it’s logical to build the world’s greatest race track here!”

Allison, Newby and Wheeler quickly bought in. In December, 1908, Fisher paid $72,000 for 328 acre Pressley Farm, 5 miles Northwest of Monument Circle, the geographic center of Indianapolis. In March 1909, he and Allison each put up $75,000 while Newby and Wheeler each put up $50,000 to capitalize the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Company.

The Indy Speedway is the simplest possible design, even less complicated than the Newby Oval, though ten times as large. Fisher planned a scale model of the track on a 20 foot patch of dirt where the Speedway Motel is today. He drove four pegs in the ground at the points of a rectangle, used a string and stick to inscribe quarter-circles in the dirt, then connected the four quarter-circles with straight lines.

The full-size product of this dusty sketch was a rectangular track with front and back straights of 5/8th mile each, end straights of 1/8 mile each and four rounded quarter-mile corners. It all added up to 2.5-miles. The original course was paved with a mix of tar and crushed stone, 50 feet wide on the straights, 60 feet wide in the corners. The corners were banked with earth at a mild angle of 9 degrees 12 minutes before being paved. Compared to the 30 degree banking at Brooklands, Indianapolis Speedway was practically flat!

Carl Fisher was the most flamboyant of the four founders, and took charge of running the new track. During the first race weekend in mid-August 1909, the tar melted, the gravel turned into slippery potholes and five people died. Fisher quickly decided a surface of small bricks would be tough, easy to repair and weather-resistant. In less than two months, Fisher’s crews repaved the entire track with 3,200,000 hand-laid bricks, each weighing 10 lbs.

Lewis Strang won the first exhibition race at the new “brickyard” on December 17, 1909, driving a 200 hp Fiat. Starting May 27, 1910, there were 42 separate races over three days. This elaborate program was repeated over Fourth of July Weekend and Labor Day Weekend.

Carl Fisher then decided that beginning with 1911, there would be just one annual race at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, a 500 miler on Memorial Day, with a stupendous purse of $27,550. Even better, the purse would increase every year to insure that the Indianapolis 500 was always the most lucrative automobile race in the world. And thus is immortality born.

Arthur Newby was a classic accountant, quiet, shy, businesslike, but remarkably astute. He never married, never wasted money and retired early to become a philanthropist, using his millions to support Indianapolis hospitals, Butler University and Earlham College. He moved to Florida and died in 1933.

Frank Wheeler was a bluff, hearty sales guy and canny investor who provided funds for inventors like Harry Stutz and George Schebler. He sold his share of Wheeler-Schebler in 1912 and retired to build a handsome estate in Indianapolis designed by Philadelphia Main Line Society Architect William Price.

Originally called Hawkeye, the Wheeler-Stokely Mansion is now a National Historic Site, as is the original Wheeler-Schebler Company building. Wheeler died in 1921. His firm was sold and renamed Borg-Warner. The winner of the Indy 500 still gets his name put on the original Wheeler-Schebler/Borg-Warner Trophy.

Allison and Fisher built side-by-side estates in 1909 next door to Wheeler’s property. Both Allison’s Riverdale and Fisher’s Blossom Heath are now part of Marian University. A brilliant businessman and consummate corporate manager, James Allison convinced his partner Carl Fisher to sell Prest-O-Lite to Union Carbide in 1917 for $9-million, just before acetylene headlamps were replaced by electric headlights.

Allison also had his own race shop, called Indianapolis Speedway Team, which among other cars, built the Peugeot-powered racer with which Howdy Wilcox won the 1919 Indianapolis 500. During World War I, the race shop changed its name to Allison Experimental, which fulfilled government defense contracts. It was reimagined again as Allison Engineering in 1920. After James Allison died in 1928, his company was sold to General Motors and eventually split into GM Aerospace and Allison Transmission.

Throughout their long partnership, James Allison was always considered the mature adult in the room, the hardheaded businessman. Carl Fisher was the impetuous boy genius, the extravagant dreamer who flitted from one idea to another, whether or not they made good business sense. True to form, Fisher was eventually worth $100-million before he lost it all in 1929.

But for three decades, Carl Fisher had a hell of a run! After creating the first nationwide automotive parts supplier with Prest-O-Lite, the first car dealership and the first speedway in North America, in 1912 Carl Fisher dreamt up the Lincoln Highway. This was a cross-country auto road from Times Square in Manhattan to Lincoln Park in Los Angeles that set the pattern for every U.S. highway since.

Fisher next organized the Dixie Highway from Detroit to Miami, then developed Miami Beach during the Roaring Twenties. Wrapped around Fisher’s own extravagant estate on Biscayne Bay, Miami Beach is still prime real estate. What is now called Fisher Island, the wealthiest neighborhood in the world, is a private island that Carl Fisher traded to W.K. Vanderbilt II in 1925 for a single yacht!

Fisher sold the Indianapolis Motor Speedway to Eddie Rickenbacker in 1927, then spent millions to develop Montauk, NY. He ended up broke, creating the Caribbean Club in Key Largo, FL as a sort of make-work project financed by sympathetic friends during the Thirties. Fisher died destitute in Miami in 1939.

On the other hand, Carl Fisher’s contributions to America are incalculable. In a very real sense, Carl Fisher founded our entire modern way of life. His Lincoln Highway and Dixie Highway provided the blueprint and directly inspired President Dwight Eisenhower to create the Interstate Highway System in 1956.

A network of limited access highways that now stretches out to 46,876 miles, this allows us to move people and cargo any place in the United States in just a few days. No exaggeration, you can thank Carl Fisher every time Amazon, UPS or FedEx delivers something cross-country straight to your door!