Event Program: 2020 Vintage Festival

Thoroughly Modern Motorcars

The annual Indianapolis 500—the “Greatest Spectacle in Racing” – wasn’t always the parade of identical “Spec Racers” it is today. Between Indy’s opening in 1909 and the last prewar race in 1941, it’s true that the vast majority of the cars that raced around the track were rear-wheel drive vehicles with the engine up front where God and Henry Ford intended it to be. But they didn’t have to be like that.

About the only things that were regulated by the Indy rules back then were engine displacement and minimum weight. Otherwise, engineers and crew chiefs were encouraged to try new ideas, no matter how outlandish. Sometimes, when somebody came up with a “genius” idea, they were right. Sometimes even more than right. Brilliant!

1913 Peugeot L7.6

In 1911, racing drivers Jules Goux, Paolo Zuccarelli and Georges Boillot convinced French auto manufacturer Robert Peugeot to bankroll the design and construction of a new racing car. They hired Swiss engineer Ernest Henry to help them. Peugeot’s professional factory engineers derisively labeled them Les Charlatans, but the quartet of amateurs created a breakthrough machine with features that are still state-of-the-art today.

The seminal Peugeot introduced hemispherical combustion chambers with a central sparkplug, gear-driven double-overhead camshafts, four-valves-per-cylinder, “desmodromic” valves that are mechanically opened and closed, cup-type cam followers and the first dry sump engine with an oil pump and remote oil tank. The Peugeot also pioneered knock-off wire wheels and adjustable shock absorbers.

Starting with the 1913 race season, Peugeot built the same basic car for years, powered by four-cylinder engines displacing 7.6, 5.6, 4.5 and 3.0-liters as sanctioning bodies demanded progressively smaller engines in a failed attempt to limit speeds. In every size, these Peugeots dominated racing worldwide.

At the Indy 500, a Peugeot was first in 1913, second in 1914 and ’15, first in 1916. There were no races in 1917 and ’18, thanks to World War I, but a Peugeot won again in 1919 and there were still 3.0-liter Peugeots in the Indy Top 20 until the Formula was reduced to 2.0-liters in 1923.

Peugeot sold identical cars to customers, with the inevitable result that they were soon competing against copies built by Sunbeam, Premier, Ballot and a host of others. But Les Charlatans had an influence way beyond simple plagiarists.

High-performance engines from the Duesenbergs and Millers of the Twenties to the Alfa Romeos and Bugattis of the Thirties to the Jaguars and Ferraris of the Fifties to the mass-produced Chryslers and Toyotas of today are still based on the innovative design perfected by Peugeot in 1913. I mean, Chevrolet just proudly introduced a dry sump engine with a remote oil tank on the 2020 Corvette, exactly like an antique, 107-year-old Peugeot. Les Charlatans, indeed!

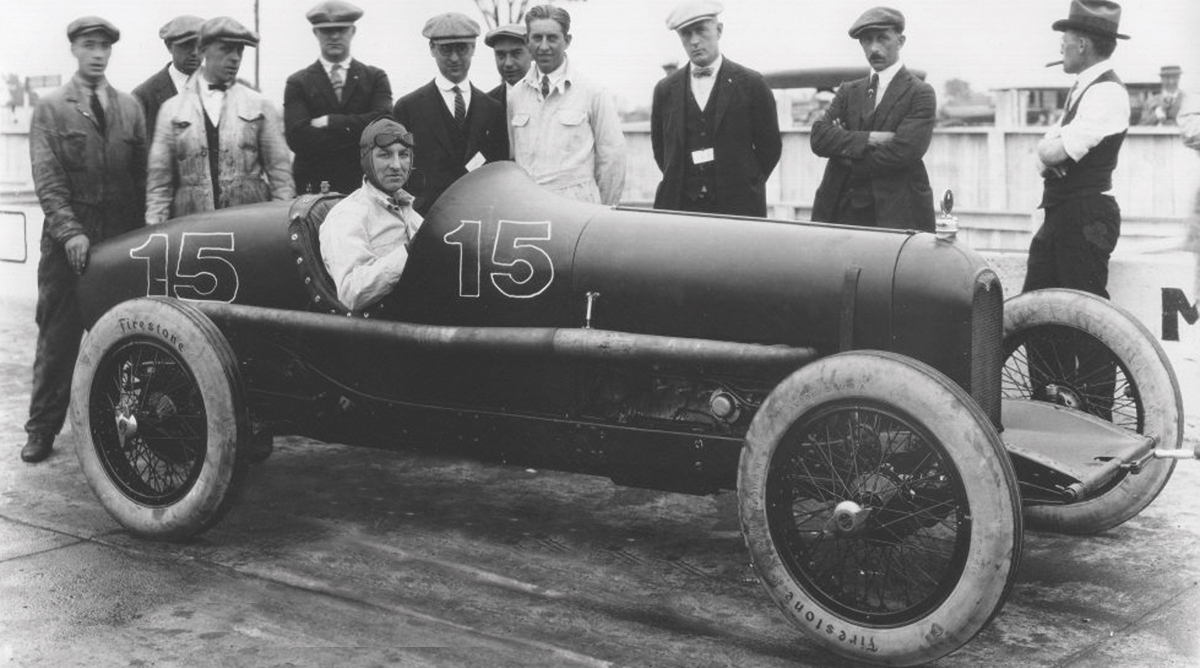

1924 Duesenberg 121

During World War I, brothers Fred and Augie Duesenberg worked with Harry Miller on an American version of a U-16 aero engine designed by Ettore Bugatti and Peugeot engineer Ernest Henry. In 1919, the Duesenbergs formed a new company to build luxury cars and Indy racers powered by an Inline-8 with a single-overhead cam and three-valves-per-cylinder. It was literally one bank of the Bugatti U-16.

In 1920, the new Duesenberg racer took over from Peugeot as the car to beat. In 3.0, 2.0 and 1.5-liter form, Duesenbergs won the French Grand Prix in 1921 and the Indy 500 in 1922, ’24, ’25 and ’27. Among other things, Fred and Augie perfected shell bearings to allow higher crankshaft speeds and four-wheel hydraulic brakes that allowed Indy racers to dive deep into the corners.

Most importantly, before the 1924 Indy 500, Fred got together with Dr. Sanford Moss, the genius who’d developed the first practical supercharger. With a large centrifugal supercharger tucked neatly beneath the updraft carburetor, Joe Boyer’s Duesenberg ran away with the 1924 Memorial Day Classic and started a trend for supercharged or turbocharged high-performance engines that continues today and will become even more important in the future.

Legend has it that the morning after the 1924 race, Harry Miller and his sidekick Leo Goossen were at the door of Allison Engineering in Indianapolis when it opened, begging for information about superchargers!

1926 Miller 91

In 1922, Jimmy Murphy replaced the engine in his year-old Duesenberg with a new 3.0-liter engine built by Harry Miller, qualified on the pole and ran away with the Indy 500. Miller combined the best features of the new Duesenberg with the best features of the Henry-designed Peugeot to create a DOHC, four-valves-per-cylinder Inline-8 that was better than either.

When the rules changed to 2.0-liters in 1923, Millers were First through Fourth, Sixth and Seventh at Indy. In 1924, supercharged Duesenbergs were First and Sixth, Millers filled the other spots in the Top Thirteen. The next year, Duesenbergs were First, Third and Eighth, Millers filled 16 of the Top Twenty-Two. For the 1926 season, the Grand Prix Formula—which included the Indy 500—was reduced to 1.5-liter (91 cubic inch) engines in cars that weighed just 1322 lbs.

Harry Miller’s masterpiece, the Miller 91, used a tiny DOHC, Inline-8 with four-valves-per-cylinder and a centrifugal supercharger to produce up to 300 hp at 8500 rpm. That’s over 3.3 hp per cubic inch! Even more impressive, Miller accomplished this with 1926 technology…leaky gaskets, primitive metallurgy, poor lubricants and low octane fuel that limited compression ratios to no more than 8:1.

In 1926, the Official World Land Speed Record was 170 mph, held by Parry Thomas in Babs, powered by a 27-liter V-12 aero engine. In 1927, the record was raised to 174.88 mph by Malcolm Campbell in his 22.3-liter Blue Bird. The same year, Indy winner Frank Lockhart took his personal Miller 91 to Roberts Dry Lake in Mojave and averaged 171.02 mph! In 1928, Lockhart geared together two Miller engines to create a 3.0-liter U-16 streamliner that was clocked at 225 mph at Daytona Beach before a tire failed and Lockhart was killed.

In 1926, the first year of the 1.5-liter Formula, there were 18 Millers in the Indy 500, many of them re-engined cars built originally for the 1923-1925 2.0-liter Formula. In 1927, 28 of 33 Indy 500 starters were Millers, in 1928, 24 were Millers, in 1929, 27 were Millers. Nobody had ever dominated Indy like this.

A Miller-powered car won Indy every year from 1922 through 1934 except ’24, ’25 and ’27 when they finished second behind a similar Duesenberg. In 1935, the Offenhauser—which was really a 1926 DOHC four-cylinder Miller engine originally intended for powerboat racing—took over Indy for the next 50 years!

By using a DeDion front suspension and front transaxle, Harry eliminated the driveshaft in his 1926 Miller 91 front-wheel drive. This allowed the driver’s seat to be dropped below the frame, lowering the bodywork—and the center of gravity—by a good 8 inches or more. Today, a front-drive Miller 91 is considered one of the most exquisite racing cars of all time, the jewel in Harry Miller’s crown.

When they were new, Indy teams preferred the conventional rear-drive Miller 91 at $10,000 to the exotic front-drive version that cost $5000 more. Miller sold 50 of his 91 cubic inch racing cars, but only a dozen were front-wheel drive. Miller’s front-drive cars often qualified on the Indy front row, but the only front-wheel drive Indy winner was Fred Frame’s 1932 3.0-liter Miller Inline-8 with tall, two-seat bodywork on a Wetteroth chassis.

You can make a credible argument that the Miller 91 FWD was simply too far ahead of its time, too advanced to be understood. Harry Miller sold his race shop in 1929, helped design the front-wheel drive Cord L-29 and at the time of his death a decade later, was just finishing the design of a small passenger car that looked much like a Volkswagen Rabbit from the 1970s, powered by a transverse-engine, front-wheel drive layout. Harry Miller was always far ahead of his time.

1935 Miller-Ford

In 1931, Miller started a new company that provided the 1932 Indy-winning 3.0-liter Inline-8 for Fred Frame’s car. Cut in half, this later became the all-conquering 90 cubic inch Offenhauser I-4 for Midget racing. In the depths of The Great Depression, thanks to a severe lack of enthusiasts with $10,000 or $15,000 to spend on a new race car, Harry Miller went bankrupt.

His friend Preston Tucker got him a deal with Ford Motor Company to build Indy racers powered by 3.6-liter (221 cubic inch) Ford flathead V-8s. The only drawbacks were that Miller had just 79 days to build 10 identical race-winners and the budget was just $2500 each.

To save time and money, Miller used a stock Ford block, crankshaft, rods and valves. Everything else was either built from scratch or a proprietary racing part—Bohnalite aluminum heads, aluminum pistons and four Stromberg Carburetors on an aluminum manifold. The result was a hot-rod Flathead Ford V-8 that cranked out 150 hp at 4500 rpm.

The racers had deep frame rails connected by tubular cross-members, a typical Miller front-wheel drive suspension and the first independent rear suspension on an Indy racer. The Ford V-8 sat “backwards” in the frame and connected directly to the two-speed front transaxle.

With no driveshaft to worry about, the driver and riding mechanic could sit on the flat floor. The aluminum bodywork was as simple as possible, with no compound curves and a cut-down 1935 Ford grille, but the Miller-Fords are still among the prettiest racing cars ever built.

Only four of the ten Miller-Fords qualified for the 1935 Indy 500, and 7 mph off the pace at that. All four retired early, because a universal joint Miller used to route the steering column around the engine overheated and seized, locking the steering. On the heels of this debacle, Preston Tucker presented Ford with a bill for $75,000, triple Miller’s estimate.

Henry Ford was so mad he locked all ten cars in a Highland Park warehouse for two years. Edsel Ford finally persuaded his father to sell nine Miller-Fords to Indy team owners Lou Fageol and Lewis Welch, who ran them sporadically at Indy until 1948, never finishing higher than mid-pack.

1938 Gulf-Miller

Gulf Oil Company decided it was important that they win the Indy 500 with a car running on pump gas rather than some explosive mixture of acetone, methanol and nitroglycerin that racers used. Despite the Miller-Ford disaster, in June of 1937, Gulf hired Harry Miller to design and build a four-car team of futuristic machines capable of attracting lots of publicity and winning the 1938 Indy 500. Miller had the full facilities of Gulf Research, 11 months and an unlimited budget. What could possibly go wrong?

Typically, rather than improve on one of the Miller-Offenhauser designs that still dominated Indy, Harry Miller decided to give Gulf a tour de force, the most advanced and wonderful racing car in the world. In 1937, the Grand Prix car to beat was the mid-engine Auto Union created by Ferdinand and Ferry Porsche, so Miller decided to build a mid-engine Indy car that would be far superior to even an Auto Union.

Miller’s mid-engine racer had four-wheel drive, four-wheel disc brakes, all-independent suspension, monocoque frame rails that were also part of the bodywork, aerodynamic fuel tanks centered in the wheelbase to maintain weight distribution as they emptied, the engine canted 45 degrees and offset in the frame to improve cornering in Indy’s left turns, inboard-mounted shock absorbers operated by remote levers, a dual-entry supercharger driven off the crankshaft, huge finned intercooler, bodywork that flares wider at the bottom to provide aerodynamic downforce, aerodynamic fairings over the drive axles, built-in multi-tube rollbars behind the driver…these are all things we take for granted now because Harry Miller thought of them more than 80 years ago!

The 1938 Grand Prix/Indy rule allowed normally-aspirated engines of 4.5-liters or supercharged engines of 3.0-liters. In Europe, Delahaye and Talbot raced unblown 4.5-liter cars that developed between 225 and 250 hp at 5000 rpm. They were hopelessly outclassed. Alfa Romeo, Bugatti and Maserati raced supercharged 3.0-liter Inline-8s that delivered between 270 and 350 hp at 6500 rpm. They were hopelessly outclassed, too. Auto Union and Mercedes raced supercharged 3.0-liter V-12s that made 470 or 490 hp at 7500 rpm and swept all before them.

Miller created a short-stroke, DOHC 3.0-liter Inline-6 designed from scratch to be both offset in the chassis and canted to the left side. The crankshaft-driven supercharger had vanes on both sides of a single rotor, with a carburetor for each entry. The blower spun at five times engine speed, or 32,000 rpm. Running on 81 octane Gulf gasoline, it produced only 250 hp at 6400 rpm.

Harry Miller was a mystic, a creative genius. He was famous for saying, “I don’t do these things. I get help. Somebody is telling me what to do.” Whoever he was, that Somebody was some intuitive engineer. What that Somebody wasn’t was a pragmatic development guy. At Miller’s shop, that role had always been filled by Leo Goossen and Fred Offenhauser.

Without his team to sort things out, Harry spent 7000 hours on each Gulf-Miller and exceeded his unlimited budget. One Gulf-Miller was finished by May, 1938, but arrived too late to qualify for the Indy 500. Three cars were ready for 1939, but Johnny Seymour crashed and the car burned. The next year, George Bailey crashed, and his car burned, too. The AAA “suggested” that the Gulf-Miller cars withdraw from Indy.

George Barringer took his 3.0-liter Gulf-Miller to Bonneville and set a record at 158 mph, which was 15 mph slower than Frank Lockhart had gone in a 1.5-liter Miller 91 a decade before. George Barringer’s car burned at Indy the morning before the 1941 race, and the last Gulf-Miller was run at Indy in 1947, completing only 33 laps.

The Gulf-Miller was probably the most technologically-advanced car to ever compete at Indy, at least 40 years ahead of its time. It was also the most expensive flop in racing history, and the only failure in Harry Miller’s remarkably visionary career. It seemed like a good idea at the time!