Event Program: 2020 Road Atlanta SpeedTour

50 Years Ago: 1970 Trans-Am

Big teams, big stars: Trans-Am’s Golden Age

By Rich Taylor

When they first thought up the Trans-Am sedan series, one of the SCCA’s great fears was that it would turn into – Oh, no! – stock car racing. But even they did not envision Rufus Parnelli Jones. Parnelli brought with him from USAC an aggression that was previously unknown to the SCCA. If you laid a fender on someone in the Can-Am, for example, you’d both end up sitting in a pile of shattered fiberglass and straw-thin frame tubes. Not to mention, you’d be asked to drive in a more gentlemanly manner.

They first thought up the Trans-Am sedan series, one of the SCCA’s great fears was that it would turn into – Oh, no! – stock car racing. But even they did not envision Rufus Parnelli Jones. Parnelli brought with him from USAC an aggression that was previously unknown to the SCCA. If you laid a fender on someone in the Can-Am, for example, you’d both end up sitting in a pile of shattered fiberglass and straw-thin frame tubes. Not to mention, you’d be asked to drive in a more gentlemanly manner.

But Trans-Am was different. Parnelli taught the road racers in stringback gloves that you could take a Bud Moore Mustang and wield it like an axe, flat laying into everything and everyone around you, and that the car would usually still be running at day’s end. The SCCA’s great fears had come true.

“By 1970, the Trans-Am was stock car racing,” says Sam Posey, “and it was wonderful! The SCCA was on the threshold of something, if they’d just been smart enough to recognize it.”

Without question, 1970 was the year it all came together, the year that saw the last die-hard fan trade in his Austin-Healey for a Camaro, that saw all four American automobile manufacturers dive into Trans-Am up to their eyeballs, that saw truly world-class racing teams exploring the boundaries of unlimited budgets. Can-Am racing may have had the unlimited rules, but Trans-Am had the unlimited money and most of the talent.

This wasn’t Bruce McLaren and Denny Hulme running over a bunch of guys in last year’s cars, this was Ford and General Motors and Chrysler and AMC battling for sales supremacy of the hottest new car market segment in the country. Road racing was a sport, but Trans-Am was a business. American Motors took the impossibly wimpy Javelin and turned it into a hot commodity, solely by having Roger Penske race it in the Trans-Am. The power of the Trans-Am as a marketing tool cannot be underestimated. (Though, of course, the SCCA consistently underestimated everything about the Trans-Am.)

Think of it: when they came to the Trans-Am, Carroll Shelby’s team had just won LeMans and the World Manufacturer’s Championship in a car of their own design, Bud Moore was one of the legends of NASCAR, Jim Hall was a great name in the Can-Am and international endurance racing, and Dan Gurney had won a Formula One race in a car built by his own team, but nobody thought that the Trans-Am was a step down for any of them. Au contraire. By 1970, the Trans-Am was equal in prestige to any race series in the world.

Three factors contributed to this. First, sales of “pony cars” went through the roof in the late 1960s. Second, marketing brand managers could prove conclusively that at least some of this sales success was due to racing. Third, no manufacturer could afford not to be in the Trans-Am, because everybody else was in the Trans-Am. It was a spontaneous reaction: racing success bred sales, which bred more competition from other manufacturers, which bred higher budgets for fancier teams, which bred more sales, more competition, more money, ad infinitum … until the whole overheated balloon collapsed in an instant. But for one brief shining moment, Trans-Am was It. That moment lasted from October 1969 through October 1970.

The SCCA helped create this memorable moment with two surprisingly wise decisions. They stabilized the rules and applied them fairly, all things considered, something that had been lacking in previous seasons. The also pulled the boring, under 2-liter sedans out of the way of the big Trans-Am racers and gave them their own separate race series. It was still considered Trans-Am U-2, but now it was just a short supporting event before the real race.

The 1970 season really started in the fall of 1969 when the reigning champions, Penske Racing, cut a 3-year, $2 million deal with American Motors to run a 2-car team of red, white and Sunoco blue Javelins for Mark Donohue and Peter Revson. Penske was a proven quantity and the team was well-funded, but it was also general knowledge that the Javelins were hopeless dogs. The morning line was that the Javelin was a handicap not even Donohue could overcome.

Penske’s defection left the Chevrolet deal open, and long-time Chevy intimate Jim Hall was the logical guy to take over. Hall’s Chaparral team would run white with blue Camaros for Ed Leslie and the patron himself, now mostly recovered from his awful Can-Am crash at Stardust in 1968. These were the Berlinetta-style second-series Camaros which, given Hall’s international reputation and Chevy’s two back-to-back Trans-Am championships, appeared to be the pre-season favorites.

For 1970, Ford cut its racing budgets by 75% across the board. In the Trans-Am, that meant that Carroll Shelby got dumped in favor of stock car racer Bud Moore, running a pair of schoolbus orange Boss 302s for Parnelli Jones and George Follmer. Conventional Wisdom said that if Ford couldn’t beat Penske’s Camaros with two teams, how did they expect to beat Chaparral Camaros with just one team?

On the other hand, Ford and Bud Moore had been racing this same basic car since 1967. In fact, they were the only team that had any prior experience with the car they’d be racing in 1970. Plus, Parnelli was the best racing driver in the series and George Follmer would have been Number 1 at almost any other team. Color Bud Moore the outside favorite.

Then there was Chrysler. Dan Gurney was already an American legend – Car and Driver had even run him for President. Compared to building your own car for Formula One or the Indy 500, winning a Trans-Am championship using $1 million of Chrysler’s money should have been a snap. Gurney severed a decade of association with Ford to put his classic navy blue and white colors on Barracudas for young phenomenon Swede Savage and for Gurney himself.

Sam Posey was another young phenomenon. In 1965, he drove his first amateur race in a Formula Vee at Lime Rock. Less than a year later, he raced at LeMans. By 1969, he was major player in F-5000 and Can-Am, and a front-runner at international endurance races in a NART Ferrari. When Dodge entrusted Sam and his buddy Ray Caldwell with their lime green Trans-Am Challenger and $1 million dollars, it seemed like a great idea. Sam was only 24, but he had yet to fail at anything he’d touched.

How competitive was the 1970 Trans-Am? Pontiac, the weakest factory team, had former Trans-Am champion Jerry Titus as the driver, wealthy businessman Terry Godsall as the team owner and now-legendary engineers Herb Adams, Paul Lamar and Dave Bean designing and building the white-and-blue cars. In any other year, this would have been an overwhelming combination.

And that’s not to mention the privateers. Among the “amateurs” were Jerry Thompson and Tony DeLorenzo in new-style, red-and-white Camaros sponsored by Owens-Corning Fiberglas. Was this a private team? Well, Jerry Thompson was a Chevrolet engineer, Chevy racing engineers like Gib Hufstader were part of the crew, Tony D’s father was vice-president of General Motors and Owens-Corning was a major automotive supplier. This same team had already won the 1969 SCCA National Championship with an A-Production Corvette, plus the GT class at both Daytona and Sebring in 1970. They were not exactly babes in the wood.

Neither were Roy Woods and Milt Minter. An amateur who’d been running SCCA Nationals and FIA endurance races, Woods moved up into the Trans-Am by the direct method of buying a pair of leftover 1969 Penske Camaros. American Racing Associates then hired experienced Trans-Am driver Milt Minter as the team leader, with Woods himself as Number 2. Little ARA turned out to be more successful than many of the factory teams with big names, new cars and big budgets. Milt Minter even won a race overall: quite a feat in a year-old, non-factory car running only a partial season.

Even a list of the truly private teams is impressive. Camaro was the weapon of choice. Former factory drivers like Bob Grossman and Craig Fisher, plus well-known amateurs like Maurice Carter, Paul Nichter, Warren Agor and Peter Schwartzott could often outlast the factory teams.

So what’s that add up to? Depth. At any given Trans-Am race in 1970, there were at least a dozen drivers who could legitimately expect to win – or more importantly, whose sponsor and team could legitimately expect them to win – and another half-dozen who were expected to do well. All of which pinpoints exactly why racing seasons like the 1970 Trans-Am are so rare.

When all is said and done, there are more losers every weekend than winners, more unhappy sponsors than happy sponsors, more disconsolate teams than victorious teams. By October 1970, the manufacturers had rediscovered that sad old adage, “if you can’t win, it’s better not to play the game.” At least not if you’re the one who has to justify a multi-million dollar racing budget to a skeptical board of directors.

But from October 1969 until the first race on April 19, 1970, there were no skeptics. Every team was a winning team, every marketing director a genius, every sponsor a savvy businessman. It was a time of unbounded enthusiasm and joyful optimism.

Let the contest begin!

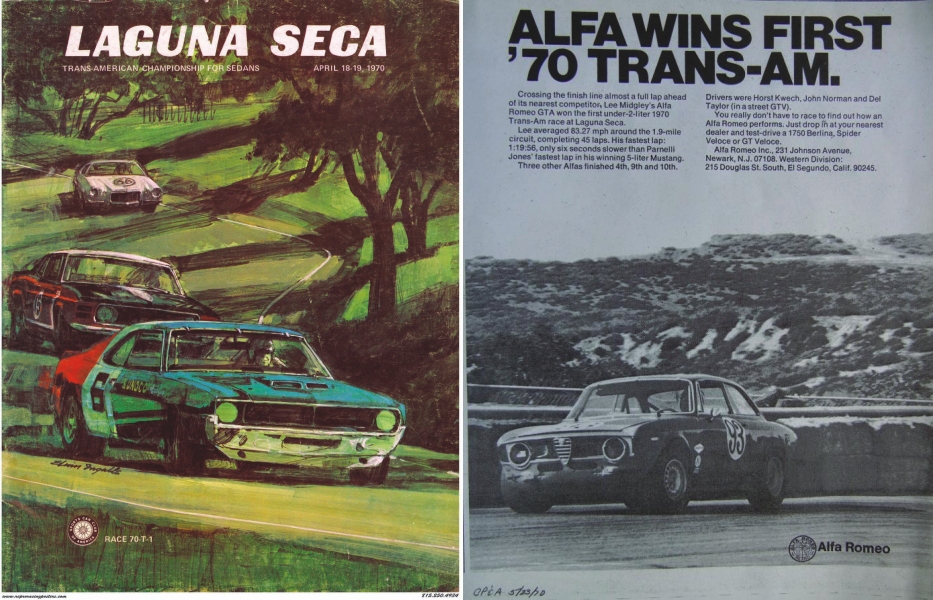

Laguna Seca—April 19, 1970

You can make a pretty good argument that the pinnacle of American road racing was reached on Sunday afternoon, April 19, 1970 at Laguna Seca in Monterey, California. The cars, team uniforms and hopeful hearts were equally unsullied. It was spring, a new beginning. Like the view from a high-altitude fighter, the racing season stretched out to the horizon, all brilliant sunlight and clean white clouds.

Everybody was there. The paddock looked like an SAE convention for famous racing engineers, the driver’s meeting was like the nominees for a Race of Champions, the pits could have been a staging area for the Miss America pageant. Not only were the Trans-Am cars and teams and drivers world-class, their womenfolk were world-class, too. As any fan will attest, that’s the one ineffable indicator of a race’s status. In 1970, Trans-Am had status.

It also had the inevitable pre-season ruckus. Because of a UAW strike, Chevrolet and Pontiac had been late getting enough cars built to homologate some parts. Neither Jim Hall nor Jerry Titus could use their rear spoilers, nor could Titus use the Firebird’s “shaker” hood. The Camaros for Jerry Thompson and Tony DeLorenzo were so late they never made it to Monterey at all.

Ford had gotten Holley to produce a giant carburetor with four barrels arranged inline rather than in the more familiar square pattern. The SCCA refused to let Bud Moore use it because it was not available to the general public. Moore had also removed the Mustang headlights and run brake cooling vents in the headlight holes. The SCCA wouldn’t let him do that, either.

No matter. The bright orange Mustangs qualified first and third around Laguna Seca’s scenic 1.9-mile course, with Donohue’s Javelin on the front row next to Parnelli and Gurney’s Barracuda next to Follmer. They were followed by Sam Posey in the Challenger and Ed Leslie in the Camaro, Titus’ Firebird and Swede Savage’s Barracuda, then Jim Hall’s Camaro and Milt Minter’s 1969 ARA Camaro. Before a single race had been run, the Laguna Seca grid was a fair indicator of how the 1970 season would shape up.

The race itself was pretty much what you’d expect. Parnelli Jones led from Mark Donohue until a round of pit stops let Mark’s Javelin past. Rufus then caught and passed Mark to win by 40 seconds. George Follmer and Swede Savage were a lap behind, Milt Minter two laps behind, Sam Posey three laps behind, Jerry Titus four laps behind. There were only 12 finishers, the rest of them private owner Camaros – and one Mustang – that were dramatically off the pace.

Among the DNFs were Craig Fisher in last year’s Camaro-based Firebird, Ed Leslie with a broken differential, Dan Gurney with a blown transmission, Peter Revson with a broken suspension and poor Jim Hall, out after only 3 laps with a blown transmission. There were some long faces and earnest discussions late into that evening.

It was already obvious that most teams had wildly underestimated what it was going to take to win the Trans-Am championship in 1970, and that they’d be playing catch-up all season. Indeed, the only teams who could feel confident were Moore and Penske – who’d picked up right where they were at the end of 1969 – and Roy Woods, who was beating the factories with his obsolete machines. Everybody else was already scrambling, and it was only April. Only 14 cars started the 85-mile U-2 race late on Sunday afternoon, and only 10 finished. The winner was local Alfa driver Lee Midgely. Four seconds behind him was Nels Miller in a BMW 2002ti, which was subsequently discovered to have oversize valves and disqualified. Don Pike’s similar BMW was awarded second, ahead of Heinz Eckhardt’s BMW, pole-sitter Horst Kwech’s Alfa and Ron Moore’s Mini-Cooper. The most significant DNFs were Vic Provenzano, who’d led the first half until his battery went dead, and Herb Wetanson, whose Alfa refused to restart after a pit stop.

Dallas 200—April 26, 1970

In the early years of the Trans-Am, they’d raced at a converted drag-strip in Green Valley, Texas. In 1970, the SCCA scheduled themselves into a brand-new facility in Lewisville, Texas. It was not to be. A Texas-size rainstorm flooded the track, turned the infield to mud and forced a cancellation of the event. Instead, the teams grabbed another two weeks to work on their cars and headed straight for a place they knew well.

Lime Rock Park—May 9, 1970

For the first time in Trans-Am history, the Lime Rock event was not taking place on Memorial Day weekend. New England fans got to see front-rank drivers like Parnelli Jones and Dan Gurney at the picturesque, 1.5-mile course. Despite Gurney’s internal problems with Chrysler, he managed to put his Barracuda on the outside pole next to Mark Donohue’s record-breaking Javelin. On the second row were Parnelli and Ed Leslie ahead of Swede Savage, Peter Revson, George Follmer, Jerry Titus, Jim Hall and Sam Posey.

This was what the crowds had come to see: five rows of factory race cars with every make represented. Independents Paul Nichter, in a Camaro, and Craig Fisher, in a Firebird, were next, ahead of a sea of independent Camaros. The only seriously unhappy campers were Owens-Corning teammates Tony DeLorenzo, who missed practice and started at the back of the 23 car field in his brand-new Camaro, and Jerry Thompson, whose matching Camaro still wasn’t ready. And of course, poor Roy Woods and Milt Minter, whose limited budget didn’t include the East Coast races.

Dan Gurney got skunked at the start, so the first lap saw Parnelli leading Mark and old pro Ed Leslie. Mark stayed near the orange Mustang until the Javelin’s overstressed engine broke after 72 laps. Gurney worked his way backwards through the field until the Barracuda’s clutch let go on lap 64.

Ed Leslie lost time when the Chaparral crew failed to replace his gas cap and he had to revisit the pits – the same crewman made the same mistake during Jim Hall’s pitstop, too – but still ended up in second place just one lap behind Parnelli, who was babying a Mustang with no front brakes and a broken pushrod. Sam Posey, the 1969 Trans-Am winner at his home track, moved carefully through the field in his Challenger to finish third, three laps behind. Jim Hall was 11 laps behind, in fourth.

Hall’s Camaro was the last factory car among the meager 10 finishers. Among the other big names, Titus stopped with a fuel leak while Follmer, Savage, Revson and DeLorenzo all blew engines as a result of oil surge in Lime Rock’s tight corners.

In the U-2 race, Gaston Andrey and Horst Kwech dominated a 16-car field with their Alfa GTAs. Third was Peter Schuster in a 2002, fourth was Harry Theodoracopulos in another Alfa. Craig Fisher, who finished eighth in the O-2 race driving his Firebird, was the only driver to compete in both events. He brought a Fiat-Abarth into sixth in U-2.

Why had the SCCA split up O-2 and U-2? Lime Rock provided a graphic answer. In the early years of the combined Trans-Am, the good-handling U-2 Alfas had been able to finish in the Top 5 at tight and twisty Lime Rock. But the Alfas were only a little bit faster than they had been then, while the big cars – thanks to factory millions – were immensely faster. In 1970, U-2 pole-sitter and race winner Gus Andrey had a fastest race lap of 1:04. O-2 race winner Parnelli Jones turned a :59.8. At Lime Rock, a 4-second difference is a lifetime. A cynic might say the tiny Alfas and BMWs were removed from the big race for their own protection.

How improved were the big Trans-Am cars in comparison to other machines? Well, in 1967 Sam Posey had been the first driver ever to lap Lime Rock in less than 60 seconds. He used a McLaren Can-Am car purposely set up for record-breaking. Less than three years later, Parnelli was lapping that fast in a 3400 lb. sedan, in traffic, while Mark Donohue sat on the Trans-Am pole with a 58.8, wrung from a lowly Javelin.

Bryar—May 31, 1970

Any conflict between Sunday’s Indy 500 and the Trans-Am was settled by scheduling the Trans-Am on Monday. At Indy, Al Unser won, driving the Ford-powered Johnny Lightning Special owned by one Rufus Parnelli Jones. Only 32 seconds behind was Mark Donohue in Roger Penske’s Sunoco Lola-Ford. Third was none other than Dan Gurney, in his own Eagle-Offy. Peter Revson was back in 22nd in his Offy-powered McLaren, while George Follmer went out after only 18 laps in Andy Granatelli’s old STP Hawk III-Ford, the same car with which Mario Andretti had won in 1969. That night, winners and losers alike hopped in corporate jets and flew to Concord, N.H., so they could be at Bryar in the morning.

The big news was that, rather than lose face continuing to trail around behind stars like Vince Gimondo or Dick Young, Dan Gurney had decided to leave his Trans-Am team in the capable hands of Swede Savage. Starting at Bryar, AAR would run a single Trans-Am Barracuda, while Daniel himself ran Indy cars, Formula One and Can-Am. It’s significant, I think, that while Gurney was a star in Indy and Can-Am, he was an also-ran in Trans-Am. It certainly wasn’t because he wasn’t comfortable racing sedans: he won the Riverside 500-mile stock car race something like five times in a row. Trans-Am was tough in 1970!

It was almost as if Gurney were prescient. Just two days after Memorial Day, on June 2, 1970, Bruce McLaren was killed while testing the new M8D. Gurney took over Bruce’s big orange McLaren and won the first two Can-Ams of 1970 at Mosport on June 14 and at St.-Jovite on June 28. Dan then got into a prickly disagreement with McLaren’s sponsor, Grady Davis of Gulf Oil, because his Castrol contract forbid him to sew a Gulf patch on his driving suit, and then Gurney, as they say, “left to pursue other interests.” Peter Gethin replaced him at McLaren, while Gurney concentrated on Formula One.

Back at Bryar, a fired-up Swede Savage drove Gurney’s #48 Barracuda instead of his own and qualified on the pole, with Parnelli on the outside front row. In the race, Jones zipped out to a solid lead. Two-thirds of the way through, however, his hood blew off and he was black-flagged. Teammate George Follmer went on to win by 3 laps over the Javelins of Revson and Donohue. Privateer Gordon Dewar’s Camaro was fourth, ahead of Jim Hall’s factory car and independent Bob Grossman in another Camaro. In seventh was Jerry Thompson in his just-completed Owens-Corning car. There were only twelve finishers out of 25 starters, and aside from the lead trio of Mustang and Javelins, all were Camaros of various vintages. To the embarrassment of Jim Hall and Tony DeLorenzo, underfinanced locals seemed at least as successful as the factory-connected Camaro teams.

The U-2 race was a cliff-hanger. Horst Kwech led in his Alfa until five laps from the end, when he ran out of fuel and had to make a quick stop-and-go at the pits. He closed back up to within eight seconds of Peter Schuster in his 2002ti. This was the first Trans-Am victory for a BMW, and other 2002s filled third through fifth.

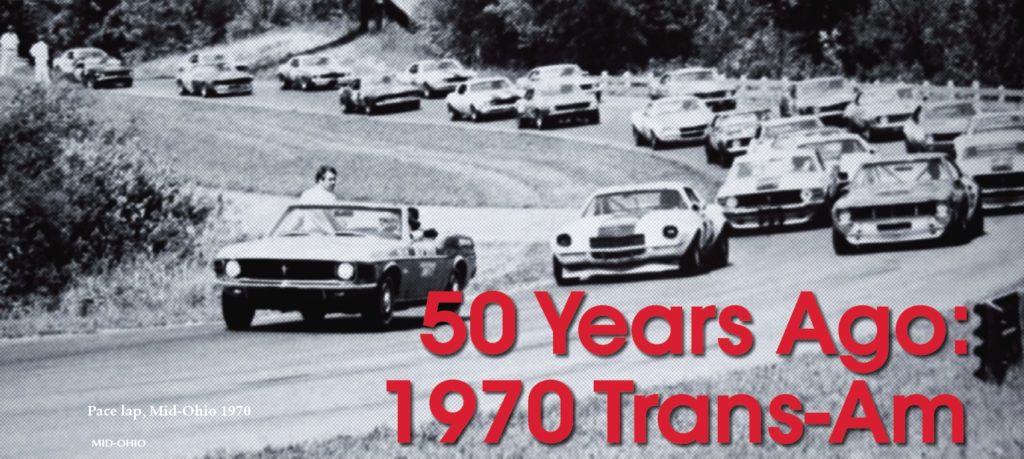

Mid-Ohio—June 7, 1970

Facing the largest field of the season so far – 30 cars – Ed Leslie put his Chaparral Camaro on the outside front row next to polesitter Donohue’s Javelin. Behind them were the two factory Mustangs. At the start, Jones and Follmer rocketed ahead and stayed ahead. After two hours of racing, Parnelli beat teammate George by 0.3 seconds. Mark Donohue’s Javelin was 78 seconds behind in third.

Three laps back was Mo Carter in a private Camaro, just 0.4 second ahead of Sam Posey’s Challenger, which in turn was just 0.2 second ahead of Warren Agor’s private Camaro in the best race of the weekend. Tony DeLorenzo in 10th was the only other well-known car among the 17 finishers.

An interesting pattern was developing. The big-budget factory teams, with their nationally-known drivers would qualify near the front of the grid, but once the racing started, the factory cars would one-by-one fall victim to brain fade or mechanical ills, leaving the field wide open for privateers in boxy old Camaros to make their way to the front.

At Mid-Ohio, for example, Jerry Thompson crashed his 1-race-old Owens-Corning car in practice, while Peter Revson’s Javelin hadn’t even completed the pace lap when the distributor drive sheared. Jerry Titus was out with engine problems after only 25 laps, Swede Savage had an oil leak, Ed Leslie blew his engine, and Jim Hall ran out of gas.

Unfortunately for the factory teams, parklike Mid-Ohio is a pleasant drive from Detroit. Almost every team had heavy-hitters from the sponsor sitting on the hillside, sipping a glass of chardonnay and watching their million-dollar investment get trounced by some guy who’d built his racer in a one-car garage and thought successful sponsorship was convincing his volunteer pit crew to buy their own hot dogs.

The withdrawal of factory sponsorship from the Trans-Am in 1971 can be traced directly to the factory team debacle at Mid-Ohio in 1970. At the same time, Trans-Am fields grew to 35 cars or more at most of the races during the remainder of the season. Obviously, SCCA A-sedan drivers all over the country looked at the results and said, “Shucks, Trans-Am can’t be that hard. Look at who’s in the Top 10! I used to beat them.”

As usual, 14 U-2 cars started the support race at Mid-Ohio, but only eight finished. Five out of six BMWs broke, while all the Alfas held together. Well-known Porsche champion Bert Everett switched to an Alfa GTA, remarked that it was “much faster” than his Porsche, broke the qualifying record and led most of the 30 laps to win over long-time Alfa stalwarts Horst Kwech, Lee Midgely and Harry T. Craig Fisher, who’d lost his Firebird ride, finished fifth in U-2, once again driving the same 1100cc Fiat-Abarth he’d had at Lime Rock.

Bridgehampton—June 21, 1970

AMC’s contract with Penske Racing had a performance clause that allowed them to cancel Roger’s factory support if Mark wasn’t winning races. After Mid-Ohio, AMC threatened to invoke this clause. At the same time, Peter Revson had a scheduling conflict, so Penske ran just a single Javelin at the next two races.

Happily, Mark Donohue was an adrenalin junkie who performed best under pressure. Bridgehamption was also something of a home course for him, a high-speed 2.85-mile circuit through the sand dunes that rewarded his smooth style. Even better, it started to rain after ten laps, which nullified the Mustang horsepower advantage and worked against the aggressively violent cornering style of Jones and Follmer.

It was classic Penske: skillful, but also lucky. After losing the pole and the start to Swede Savage, Mark came back from third thanks to a superb Penske pit stop, then stretched his lead when Savage blew his differential, Parnelli spun in the rain and Follmer was incorrectly black-flagged.

At the end of a long, wet day, it was Donohue winning by more than two laps over Follmer and Jones, with Jim Hall four laps behind. Hall in fourth was the last factory car still running in a field of 18 finishers. Maurice Carter and Peter Schwartzott were the leading independents, driving Camaros.

In the late-afternoon U-2 race, after a 100-mile battle, Hans Ziereis kept his BMW three seconds ahead of Horst Kwech’s Alfa using some fairly obvious blocking in the closing laps. They were followed by Schuster’s BMW and Midgely’s Alfa. For the first time in four years, U-2 was a competitive series, now that the Porsches had been removed. Still, only 10 cars finished out of 15 starters. The important departures were Bert Everett in an Alfa and Russ Norburn in a BMW, both of whom spun out on the damp track and got stuck in Bridgehampton’s infamous sand.

Donnybrooke—July 5, 1970

Donneybrooke was the turning point of the season and, in many ways, the most entertaining race of the year. Swede Savage grabbed his third pole with the obviously quick but fragile Barracuda, with Parnelli’s Mustang on the outside. Ed Leslie’s Camaro and Follmer’s Mustang were on the second row ahead of Sam’s Challenger and Mark’s unusually-slow Javelin. Ailing Jim Hall had replaced himself with Indy star “Pelican Joe” Leonard, who qualified next to Milt Minter in Roy Wood’s 1969 Penske Camaro. After a budget-forced hiatus, cash-poor ARA was back – and with a vengeance.

Sam Posey was out after only 13 laps, followed one lap later by Donohue when his engine let go. Ten laps later, Jerry Titus blew, followed soon thereafter by Tony DeLorenzo who crashed, Ed Leslie who engine let go and Parnelli Jones whose suspension collapsed. Swede Savage had his best afternoon to date, leading for the first half until he got his transmission jammed in Second gear. He continued on, finally finishing fifth, 3 laps behind.

One lap ahead of Savage was Pelican Joe in the #1 Chaparral. Ahead of him, however, was an astonishing sight. Amateur Roy Woods, Jr. was in third, two laps behind the leaders, driving an old-style Camaro. At the front of the pack was an even more astonishing sight: George Follmer in the factory Mustang door handle to door handle with cagey Milt Minter in Roy Woods’ second 1969 Camaro. On the last lap, Minter and Follmer rubbed fenders in true stock car fashion, and in a rare instance of poetic justice, the rough-driving Follmer was shoved back into second.

Minter blasted across the finish line in his year-old, private entrant ARA Camaro to a standing ovation from the crowd. It was the first time a privateer had won a Trans-Am since Bob Tullius won at Daytona in February, 1967, driving his year-old Dodge Dart.

The best part happened after the race. Follmer, who was infamous for both his volatile temper and his aggressive tactics, filed a protest with the stewards against Minter’s rough driving. It was an opportunity too good to miss. The stewards not only disallowed Follmer’s protest, they fined him $100 for unsportsmanlike conduct.

In the U-2 race, Horst Kwech and Harry T in Alfas led Russ Norburn and Don Pike in BMWs. There were only seven finishers from 14 starters. At halfway point in the season, thanks primarily to Herb Wetanson’s two-car team, Alfa-Romeo led BMW by 48 points to 32 points, while Craig Fisher had earned 3 points for Fiat-Abarth.

In O-2, thanks to Milt Minter and the host of other Chevrolet privateers who supplemented the lackluster Chaparral and Owens-Corning teams, Chevrolet was only 21 points behind Mustang’s 48 points, and two points ahead of AMC’s 25. Sam Posey had earned all of seven points for Dodge; Gurney and Savage only five points for Plymouth. Poor Jerry Titus had yet to finish in the Top Six, giving Pontiac zero points for the season.

Elkhart Lake—July 19, 1970

The one thing everyone remembers from the 1970 Trans-Am is that Jerry Titus was killed at Elkhart Lake. Titus crashed in practice on Saturday when the steering failed on his new Firebird and he went straight into a bridge abutment in a high-speed area called Thunder Valley.

It took Jerry seventeen days to die of his injuries, so that during the rest of the weekend, while his friends knew the accident had been serious, they were not unduly alarmed. Racing drivers crash every weekend and they figured he’d be back by the time they got to St.-Jovite for the next race. The Milwaukee hospital even described his condition as “satisfactory.” Every person in the pits had at least one friend who’d been in worse shape than that and come back with no problems.

Including Jerry’s Firebird, there were 37 entries, the biggest Trans-Am field of the season. The Mustangs of Jones and Follmer sat on the front row, thanks to impressive top-end power that made all the difference on 4.0-mile Road America’s long straights. At the start, however, Ed Leslie tried to jam his Chaparral Camaro between Jones and Follmer as they went into Turn One. Follmer crashed, Leslie was black-flagged and Jones continued on until he lost the lead during a tire change.

The new leader was Sam Posey, thrilled to be out front for the first time all season and equally pleased with his choice of Carroll Smith to replace Ray Caldwell in the pits. Sam built up a half-minute lead, which he promptly lost once pit stops began. How? Roger Penske had come up with yet another “unfair advantage.”

In Trans-Am – like NASCAR – because all the cars were so similar, they all needed to pit for tires and gas at roughly the same time. There were always traffic jams in the pits plus cars of wildly different speeds getting bunched up when they left the pit lane. Roger cagily had Donohue and Revson start the race on half-full tanks. Donohue came in after only 10 laps, when the pits were empty, and got away onto a clear track, half a lap behind the pack. While they pitted, he inherited the lead. While he pitted, they all stacked up racing against each other. It worked a charm. Donohue hardly saw another car all afternoon and won by 58 seconds over Swede Savage and 90 seconds over early leader Sam Posey. Jim Hall had put himself back in the Chaparral and was fourth, again, ahead of Parnelli. In sixth and seventh were Milt Minter and Roy Woods in their amazing 1969 Camaros, well ahead of Tony DeLorenzo and Warren Agor in their 19701/2 models. Once again, there were only five factory cars out of 25 finishers.

Out of 36 starters, there were three Javelins, one Barracuda, one Challenger, five Mustangs, Dan Speigel’s Chevy II, and 24 Camaros. Obviously, thanks to Chevrolet’s comprehensive racing catalogue and a vast aftermarket, almost anyone could put together a Camaro and become a professional Trans-Am driver. That some of these cars didn’t belong in an SCCA National was beside the point: their drivers were professional racers, even if they won the minimum $50. In terms of getting the maximum exposure out of the Trans-Am for the minimum investment, Chevrolet was way ahead of the pack.

The now customary 14 racers started the 100-mile U-2 race, but only nine finished. Horst Kwech won again in Herb Wetanson’s Alfa GTA, handily beating Peter Schuster and Russ Norburn in BMWs. Long-time Alfa pilot Ed Wachs was fourth. Lee Midgely, who’d run up front all season, blew his Alfa’s engine after only 2 laps.

Mt.-Tremblant St.-Jovite—August 2, 1970

A curious weekend. Tough Jerry Titus was still fighting for his life in St. Joseph Hospital back in Milwaukee – he wouldn’t die until the following Tuesday – Vic Elford was in Jim Hall’s Chaparral Camaro and the incomparable A.J. Foyt was in Bud Moore’s backup Mustang. Because of official dithering – they’re French, you know – the race started two hours late, with Parnelli and Mark on the front row ahead of Follmer and Ed Leslie, Sam and Swede Savage, Revvie and Elford. Parnelli had crashed A.J.’s car in practice, so Foyt was a spectator even before the racing began.

No matter. Roger Penske was still using his staggered pit stop strategy, bringing Mark in after only 14 laps, but putting him in the lead when everyone else pitted 10 laps later. At the end of 70 laps, having passed almost no one important, Mark had cruised to nearly a lap ahead of George Follmer and Parnelli Jones, with Sam Posey in fourth, Peter Revson in fifth and independent Camaro driver Maurice Carter in sixth – the highest placed of 22 Camaros at St.-Jovite.

In U-2, the Alfa GTAs blew away the BMWs, with Lee Midgely and Horst Kwech at the head of the line. Bert Everett grabbed the pole, the U-2 track record and the race’s fastest lap in his Alfa, but a flat tire moved him back to eighth at the finish.

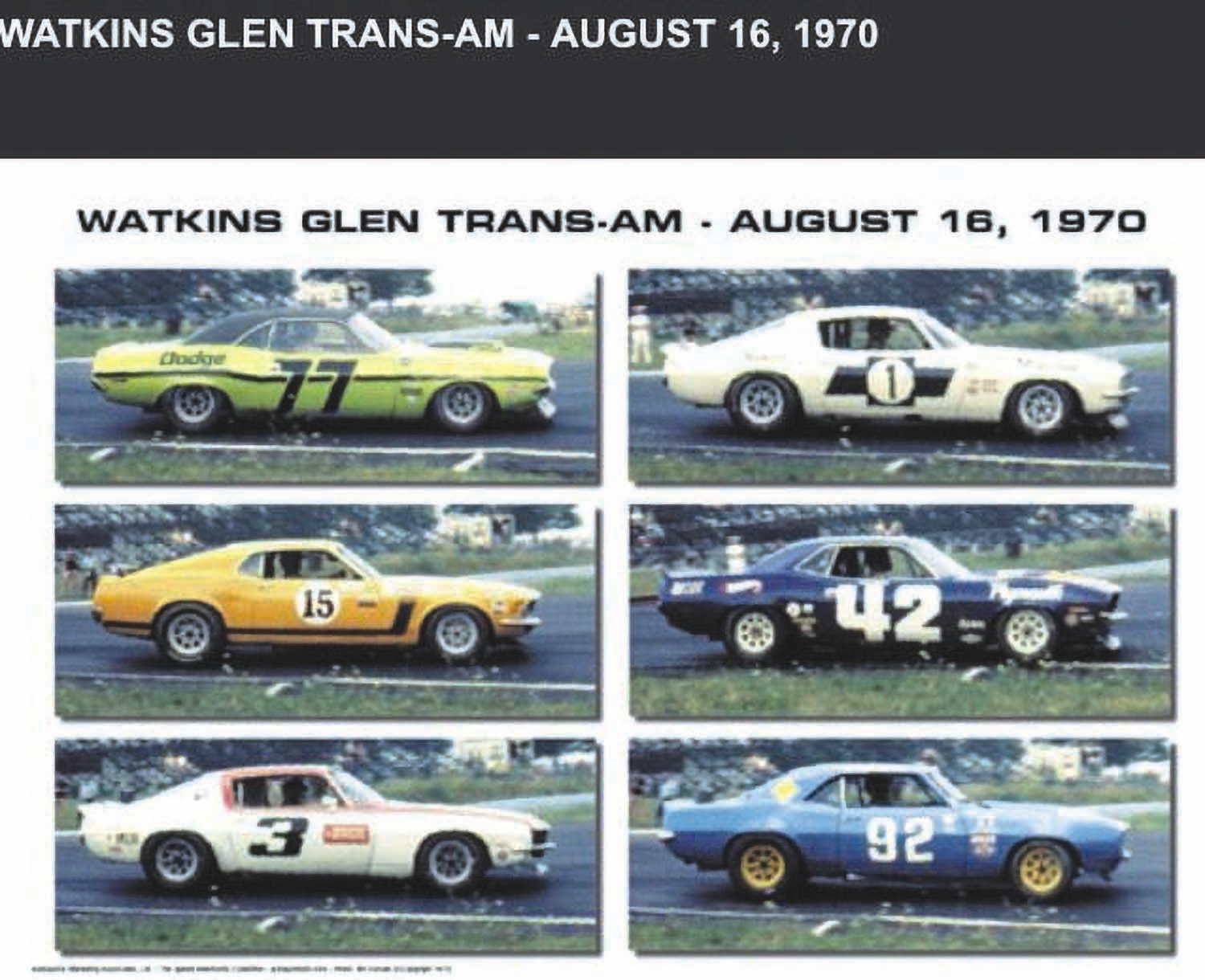

Watkins Glen—August 16, 1970

There were two upsets in the Trans-Am in 1970: Milt Minter won with his ARA Camaro at Donnybrooke and Vic Elford won with his Chaparral Camaro at Watkins Glen. It was a far cry from 1968 and 1969, when it was an upset if Mark Donohue’s Penske Camaro did not win. Was Penske Racing bigger than Chevrolet? Roger sure won more races.

Elford’s ally, just as it had been for Donohue at Bridgehampton, was rain. Rain neutralizes horsepower and rewards cornering skills. At the Glen, Elford started third, behind Donohue and Parnelli, next to Sam Posey, ahead of Swede and Revvie, Ed Leslie and Follmer. Parnelli led from Mark for the first thirty laps until the rains came. From fifth, Elford then worked his way past them on the slick track.

After a near-the-end round of pit stops to switch back to slicks on the drying track, Elford was able to hold on to first by 9.8 seconds over a rapidly-closing Mark Donohue. Follmer was third, two seconds behind Mark, having been passed on the last lap when his Mustang sputtered on an almost empty tank. Parnelli was half-a-minute behind Follmer, an equal distance ahead of Revvie, Savage and Leslie, in that order. Once again, Mo Carter was the leading independent Camaro, followed by DeLorenzo, Minter and the field.

Among the names in the DNF column, Roy Woods was already gone on Lap 2, Warren Agor on Lap 15, Sam Posey on Lap 24, Jerry Thompson and Bob Grossman on Lap 54, John Cordts on Lap 78. Out of 35 starters – 45 cars had shown up for qualifying, a record for a non-endurance race Trans-Am – there were 21 finishers. The top seven finishers were factory cars, which was also a record. Indeed, Sam Posey in the Challenger and John Cordts in Terry Godsall’s Firebird were the only factory DNFs.

Horst Kwech won the one-hour U-2 race in his Alfa, beating Lee Midgely by 64 seconds in a sister car. There were a record 18 starters; eight Alfa GTAs, five BMW 2002s, two Volvos, a Ford Escort, a Fiat-Abarth and a Mini-Cooper. But as it had been all summer, the contest was between Alfa and BMW. And Alfa was winning.

Pacific Raceways—September 20, 1970

Contract time. Just about every team was hearing some version of “if you guys expect to go racing next year, you’d better win some races!” As a result, Dan Gurney rehired himself to join Swede Savage in the second Barracuda, Sam Posey hired Ronnie Bucknum to drive a second Challenger and Terry Godsall put David Hobbs in the back-up Firebird as a teammate for John Cordts.

No matter. Parnelli Jones won the 1970 Trans-Am Championship for Ford by starting from the pole at 2.25-mile Pacific Raceways, leading nearly every lap and finishing 19.6 seconds ahead of Mark Donohue’s Javelin. Sam Posey was a lap behind, and then came Follmer in the second Mustang, Vic Elford and his teammate Ed Leslie in the Camaros and Peter Revson in the second Javelin. Once again, Mo Carter was the top independent Camaro, ahead of Milt Minter.

Both Barracudas blew their engines, as did both Owens-Corning Camaros, Roy Woods’ Camaro and Ronnie Bucknum’s Challenger. Both Pontiacs were also gone early – Cordts was disqualified for getting a jump-start during a pit stop, Hobbs broke after eight laps – as TG Racing continued the most disastrous season any race team ever suffered. At this point, most everybody just wanted to get the year over with and go home.

U-2 was also decided at Kent. Alfa Romeo had enough points, thanks to another win by ex-Porschiste Bert Everett over Don Pike’s BMW, that BMW could no longer catch them. The 16 car U-2 field contained most of the usual suspects with the exception of Craig Fisher’s missing Fiat-Abarth. New additions were Walt Maas in a 2002ti and Jim Rogers in the first of the soon-to-be all-conquering Datsun 510s.

Riverside—October 4, 1970

The championship had been decided, but the factory deals for 1971 were still very much up in the air. To that end, Tony Adamowicz replaced Ronnie Bucknum in Sam Posey’s second Challenger and Jerry Thompson replaced John Cordts in the second Firebird. Thompson was available because Tony DeLorenzo decided not to bring the Owens-Corning cars to Riverside. Instead, he used the time and money to prep the team’s Corvettes for the SCCA Runoffs.

The only other interesting additions among the 35 qualifiers were Corvette racer Dick Guldstrand driving a private Mustang prepared as an engineering project by students at Chaffey College and quirky Chevrolet engineer Paul Van Valkenburgh who raced his own 1967 Camaro, a quasi-street legal car that he drove to the track.

Oh, yes. Just before the start, Dan Gurney announced that this would be his last race; he was retiring to become AAR’s team owner/manager and would concentrate on building Eagle Indy cars. After the season ol’ Daniel had been having, nobody was particularly surprised.

The year ran out true to form. Parnelli broke the Trans-Am track record in qualifying and led until he clipped a back-marker while lapping. The resulting spin into the desert moved Rufus back to ninth. No problem. He set the fastest race lap, passed the field and went on to win by nine seconds over his teammate George Follmer and 29 seconds over Mark Donohue.

Too late to salvage the season, AAR was finally able to keep two cars together. Savage and Gurney finished fourth and fifth, ahead of Ed Leslie’s Chaparral Camaro and teammates Milt Minter and Roy Woods in their 1969s. David Hobbs kept the TG Firebird together to finish ninth, its first finish since Jerry Titus’ seventh at Laguna Seca in the first race of the season. Van Valkenburgh brought his ancient Camaro into 14, then drove it home again, proving … uh … something.

As usual, a raft of factory cars blew their engines, including Vic Elford, Tony Adamowicz and Jerry Thompson. Sam Posey had a differential let go. Peter Revson was involved in two different accidents, blamed his troubles on Sam and ended his frustrating afternoon with a widely-reported wrestling match in the pits. Posey’s team owner Ray Caldwell calmly watched his driver being strangled at his feet until team manager Carroll Smith broke it up.

U-2 ran true to form, too. Bert Everett led Horst Kwech, both in Alfas, over Don Pike’s BMW and Tony Adamowicz in another Alfa. Eleven of the 17 starters were in Alfas, four in BMWs, one in a Ford Cortina, one in a Mini-Cooper.

Once the SCCA had thrown out two finishes as per the rules, Alfa-Romeo had earned a perfect 81 points. BMW had 52 points, Fiat-Abarth and BLMC earned three points each. Had there been a driver’s championship, Horst Kwech would have won. He finished every race in the top four, with one fourth, one third, six seconds and three wins.

In O-2, the contest was much closer. On the basis of their best nine finishes, Ford earned 72 points, AMC 59, Chevrolet 40, Dodge 18 and Plymouth 15. If there had been a driver’s championship in 1970, using the 1971 scoring system, Parnelli Jones would have beaten Mark Donohue by just one point, 142 to 141. George Follmer would have been third, Sam Posey fourth.

Ten days after Riverside, the SCCA announced its final season figures. A total 210,000 spectators had watched 11 Trans-Am races, an average of 19,000. This was up from 1969, thanks to lots of factory publicity, big name drivers and exciting racing. The tracks paid out a total purse of $270,300, of which Parnelli Jones took home $26,600 – about 1% of what it cost Ford and Firestone to win that amount. Contingency awards added another $112,450 to the total take, up from just $51,250 in 1969. Some 318 O-2 cars and 169 U-2 cars competed in 1970, for an average starting grid of 28 and 15, respectively. All healthy news.

Little did anyone suspect that they had just watched the last race of Trans-Am’s Golden Era.