Event Program: 2025 NOLA SpeedTour

DESTINATION: CAJUN COUNTRY

Laissez Les Bon Temps Rouler!

The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht ended the War of the Spanish Succession, a war that engulfed virtually all the European countries and their colonies around the world. It’s way too complicated to get into here, but one result was that in North America, Spain ended up with control of what today is Florida, Mexico and part of the American Southwest, while Britain got its East Coast Colonies from Maine to Georgia, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and parts of Northern Canada around Hudson’s Bay.

France was granted a huge swath of land from the Arctic Circle to the Gulf Coast of Texas, from the Appalachian Mountains to Saskatchewan, plus what are now Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton Island.

Among the many problems caused by the Treaty of Utrecht, England ended up with part of Eastern Canada, then known as Acadia, that had been in the possession of French settlers for generations. When the next conflict between France and Britain came along—the Seven Years War of 1754 to 1763, known to Americans as the French & Indian War—some of the feisty French inhabitants of Acadia understandably conducted guerrilla warfare against the British.

The British reacted by deporting nearly 12,000 French settlers. Many of these Acadians eventually made their way via France to Southwestern Louisiana, where they established what is now called Acadiana, populated by French-speaking Cajuns…Acadian>Cadian>Cajun…get it?

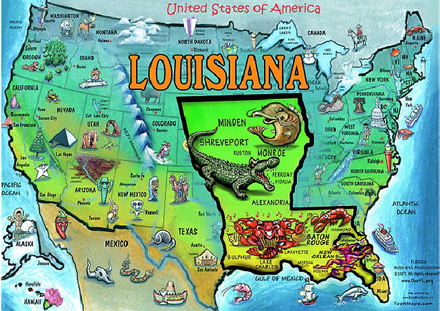

Today, twenty-two of Louisiana’s sixty-four parishes (counties) are Acadian, a strip about 100 miles wide stretching from New Orleans to Texas along the Gulf Coast. Roughly 1.4-million people live here along the bayous. There are three sizeable metro areas—Lafayette, Lake Charles and Houma-Thibodaux—which thanks to our homogenizing McDonald’s culture mostly look like cities anywhere else in the United States. To find what’s left of the unique Cajun culture, you have to search.

Today, twenty-two of Louisiana’s sixty-four parishes (counties) are Acadian, a strip about 100 miles wide stretching from New Orleans to Texas along the Gulf Coast. Roughly 1.4-million people live here along the bayous. There are three sizeable metro areas—Lafayette, Lake Charles and Houma-Thibodaux—which thanks to our homogenizing McDonald’s culture mostly look like cities anywhere else in the United States. To find what’s left of the unique Cajun culture, you have to search.

Depending on which is the most convenient way for you to exit New Orleans, you can hop on Interstate 10 West and take it to Lafayette, take I-10 to I-310 to Highway 90 or take Business 90 to 90 to Lafayette. This part of Louisiana is a huge alluvial fan formed at the mouth of the Mississippi River. It’s all low-lying wetlands, and what few local roads there are tend to go North-South and stop when they reach the shore of the Gulf of Mexico. The East-West highways are mostly elevated above the bayous where it’s often tough to tell where the water ends and land begins.

Many Cajuns are bilingual, switching effortlessly from drawling English to Baroque French, often in the same sentence. Most are also Roman Catholic, a notable distinction in the predominantly Protestant Bible Belt. As a general rule, most Cajuns you meet will also be friendly, fun and talkative to the point of garrulousness. Even when they’re working, they’re having a good time!

Start by visiting Acadian Village in Lafayette (337-981-2364, acadianvillage.com). This is a typical Cajun village as it would have looked around 1850, made up of eleven authentic buildings from around Acadiana, brought together and restored. There’s a church, seven homes, a blacksmith shop, a doctor’s office and a schoolhouse.

There are interesting exhibits about traditional Cajun music, art, weaving and building with hand-hewn cypress, insulated with bousillage entre poteaux (mud between the posts). The whole town gets decorated in lights for the month of December, turning into Noel Acadien au Village with Cajun dances, craft fairs, food and wine festivals, etc. It’s a continuous Cajun party that goes on for a month!

A little more background. The expulsion of the Acadians by the British is a minor footnote to the French & Indian War, which itself is a minor footnote to the worldwide Seven Years War. It was all pretty much forgotten by the world until 1847, when Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published a long epic poem in dactylic hexameter called Evangeline. About the only thing most people have ever heard from Evangeline is the opening line, “This is the forest primeval…” and not one in a hundred could tell you what it’s from.

Evangeline is romantic clap-trap. Young Evangeline Bellefontaine loves Gabriel Lajeunesse, but they’re separated when the British deport the Acadians. After decades of adventures, Evangeline is working as a Sister of Mercy in Philadelphia. She finds Gabriel, whom she hasn’t seen in literally a lifetime, who is sick and dies in her arms.

Starting in 1907, Louisiana Judge Felix Voorhies wrote a number of books, now debunked, claiming that he’d found the real historical figures upon which Longfellow based his poem, Emmeline LaBiche and Louis Arceneaux, and that they had met in St. Martinville, LA where she died. Not coincidentally, St. Martinville was where the Judge lived.

Immensely popular in the nineteenth century, Longfellow’s poem inspired a 1929 Hollywood tear-jerker called Evangeline, inexplicably starring Mexican bombshell Delores del Rio. To help publicize the film, the studio paid for a life-size statue of del Rio dressed in her modest Evangeline peasant costume—including wooden shoes—which was then presented to the town of St. Martinville.

Fictional or real, Evangeline/Emmeline became a potent symbol, inspiring the Cajuns of Louisiana to unite, form Acadiana, design their own flag and preserve their unique, fun-loving culture. Just 17 miles from Lafayette, tiny St. Martinville has now become the Center of Cajun Country.

There’s a pretty little square that’s the St. Martinville Historic District, listed on the National Register. There’s the picturesque church of St. Martin de Tours, an Acadian Memorial Museum, the statue of Delores del Rio and a huge old oak tree, now known as the Evangeline Oak, where the Judge claimed Emmeline LaBiche and Louis Arceneaux met in old age. Usually, there are a few local musicians enthusiastically playing on the green, and it’s all about as quaint and picturesque as can be. There’s even a St. Martinville Tourist Center (337-394-2233, stmartinville.org).

Just 1.5 miles from St. Martinville along Route 31 on Bayou Teche is Longfellow Evangeline State Historic Site (337-394-3754, crt.state.la.us) that dates back to 1934, soon after the statue of Evangeline/Emmeline showed up in St. Martinville. There’s a 1790 Acadian cabin, an authentic Acadian farmstead and 1815 Maison Olivier, built by a wealthy Creole plantation owner. The three buildings comprise a perfect lesson in the historic difference between the poor and homeless Acadians and often wealthy Creole planters, many of whom were of African descent.

Today’s party-loving Cajuns are primarily known for two special things; music and food. A Cajun tradition is the “Bal de maison,” an all-night dance party that goes on till dawn. Traditional Cajun music is related to French folk music, the haunting ballads and lively dance music of Normandy and Brittany. Early Cajun ballads were sung a cappella.

Dance music was often played on twin fiddles, and authentic Cajun music relies on three simple instruments; accordion, fiddle and metal triangle, plus the human voice. Amede Ardoin, Dewey Segura, Joe and Cleoma Falcon and the Breaux Brothers are among the best known old-time Cajun performers.

Add a piano and steel guitar, and you get Country Cajun, not unlike Texas Swing. Bands like the Red Stick Ramblers and Lost Bayou Ramblers are typical of Country Cajun. Fais-do-do, or Dancehall Cajun adds drums, bass guitar and rhythm guitar to the basic Cajun instruments, at least partially to produce enough volume to fill a large dancehall. The Basin Brothers are a typical fais-do-do band.

Today, Cajun performers have blended zydeco, blues and soul into traditional Cajun music, adding instruments like the harmonica, electronic keyboard and old-fashioned washboard. Performers like Wayne Toups, Lee Benoit and the Mamou Playboys are popular Contemporary Cajuns. My personal favorites are Joe Douglas and the American Cajun Band.

Cajun music is everywhere in Acadiana, in dance halls, bars and restaurants. Ah, Cajun restaurants. Made famous by chefs like Emeril Lagasse, John Besh and Kevin Diez, it’s far more than the spicy burned fish that Paul Prudhomme made popular.

Traditional Cajun cooking is really French peasant cooking, related to the cassolette. There’s sometimes a separate pot of vegetables, flavored with onion, celery and green peppers. There might be a pot of steamed rice, and a third pot with pork, shrimp, whitefish or whatever is available to form an entrée. Cornbread often replaces rice.

Usually, meat is barbequed, smoked or cooked slowly at low temperatures for hours. Local crabs, crawfish and shrimp are boiled, and every chef has a secret recipe for making sausage…Andouille, Boudin or Chaurice. Wild game, including squirrel, rabbit and frog were all part of French peasant diets, and Cajun, too. You’ll often find alligator and snake on restaurant menus; both really do taste like chicken, and often probably are!

Cajun specialties include the thick soup called gumbo and a French version of Spanish jambalaya, which cooks rice, meat, seafood, vegetables and lots of spices all together in one pot. Cajun cuisine depends on spices, and it’s really the blend of spices that differentiates the chef. French-style Herbes de Provence is just a starting point; Cajun cooks add much stronger tasting cayenne pepper, garlic, paprika, green onions and Tabasco.

If there’s one thing that symbolizes Cajun joie de vivre, it’s the Crayfish Boil. In one pot, one boils whole crayfish, shrimp, crabs, whole potatoes, onions and corn on the cob, seasoned with cut lemons, mustard seed, cayenne pepper and the chef’s favorite blend of spices. Washed down with beer, wine or homebrew moonshine, accompanied by a good pair of fiddlers and a classic accordion, a Cajun Boil can go on for days.

Laissez Les Bon Temps Rouler!