Event Program: 2025 Road America June SpeedTour

FOUNDERS: JOHN AND PEG BISHOP

Founders: John and Peg Bishop

By Rich Taylor

Like many other enthusiasts, Syracuse University art student John M. Bishop saw his first sports cars race at Watkins Glen. This was in 1950, when The Glen was still using the 6.6 mile “round the houses” circuit. After graduating, Bishop worked for Sikorsky Aircraft, but spent his weekends as a volunteer at SCCA events. In the evenings, he created artwork of racing cars, which he sold through the busy R. Gordon automotive book store in Manhattan.

In 1956, Bishop was hired full-time to head the SCCA Contest Board. The SCCA was transitioning from racing on public roads and SAC airbases to purpose-built courses like Elkhart Lake and Lime Rock Park. At the same time, professional racing drivers, particularly John Fitch, were trying to get the determinedly-amateur SCCA to allow paid professionals to race in their events.

Not only a well-known international racer, John Fitch was also Managing Director of Lime Rock. As he loudly complained, “The SCCA has a monopoly on road racing. They’re completely unrealistic about the whole thing. The best racing drivers in the world, my friends Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss, cannot race in America. It’s nutty!”

In 1958, Fitch got together with USAC and obtained approval from the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile to conduct road racing events that were open to both amateur and professional drivers in the United States. Within two years, this blossomed into an entire sports-racing series sanctioned by the FIA that included the LA Times Grand Prix and bracketed the US Grand Prix.

In 1962, John Bishop took over as SCCA Executive Director. He was forced to fight against traditionalists who still wished to perpetuate the rules inherited from nineteenth century British horse racing, rules that protected gentlemen amateurs against competition from hired ringers.

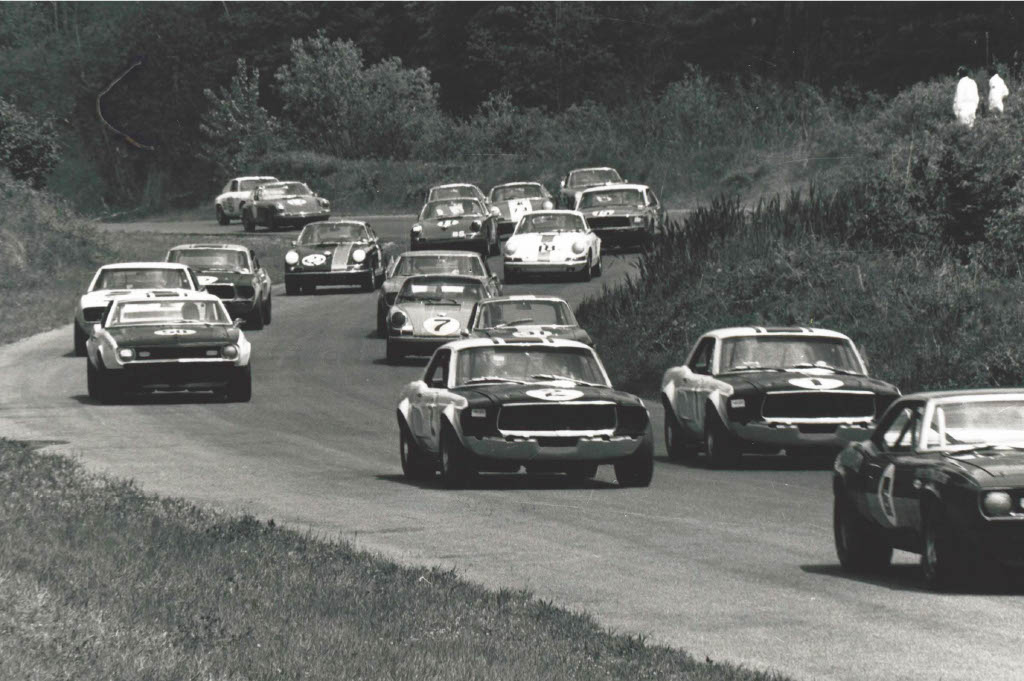

Bishop was forced to compromise. The SCCA would continue to hold Regional and National Championships intended for amateur drivers, but a new United States Road Racing Championship would begin in 1963, an eight-race series for the same sports-racing cars that were being raced by professionals in the USAC series wrapped around the LA Times Grand Prix. The USRRC was so successful, in 1966 John Bishop was finally able to convince the SCCA to let him put together a professional racing division. The first of these series was the Canadian-American Championship—Can-Am—run to the rules of FIA Group 7, Appendix J. Can-Am was the best road racing series ever, because at least at the beginning, “the only rule is there are no rules!” Can-Am was an absolutely mind-boggling display of unlimited horsepower in some of the prettiest, fastest cars ever designed.

John Surtees won the first Championship with a Lola in 1966, virtually identical McLarens won 37 of the 43 Can-Am races held in the next five years, after which George Follmer and Mark Donohue in Penske Porsches ran away with the series until it expired from ennui.

In 1966, John Bishop also consolidated all open-wheel racers into three groups; Formula C for 750 lb. cars with production-based 1100 cc engines, Formula B for 848 lb. cars with production-based 1600 cc engines and Formula A for cars that weighed at least 1105 lbs. and could be powered by a variety of supercharged “pure racing” engines of less than 3.0-liters or cars that weighed at least 1250 lbs. powered by 5.0-liter production-based engines.

In 1969, the SCCA Grand Prix Formula A Championship began, quickly renamed Continental Pro-Formula Championship and then Continental 5000 Championship. Like the Can-Am, Continental attracted the best drivers in the world, wheeling Formula cars which were essentially identical to the cars that they drove in Formula One or the Indianapolis 500.

After a rather lukewarm start, the glory days of Continental were 1971 through 1973, sponsored by L&M Tobacco. Continental Championships made the reputations of David Hobbs and Brian Redman, but after L&M took their money elsewhere, Continental, as General Douglas MacArthur was famous for saying about old soldiers, “just faded away.”

Ironically, when John Bishop came up with SCCA’s three professional series, he expected sports-racers and open-wheelers to be the stars. A third series, for sedans, was essentially a ploy to get auto manufacturers involved racing production cars that the general public could recognize. At the time, racing full-size sedans on a road course seemed too much like NASCAR.

So the SCCA divided sedans into four classes, the same way they’d divided sports cars and open-wheelers. The professional series would be for Group B sedans with engines under 2.5-liter and Group A sedans, 2.5 to 5.0-liter. Since the series was scheduled to race everywhere from Sebring to Riverside, it was called Trans-American Sedan Championship, or Trans-Am. And thus is immortality born.

Thanks to car manufacturers battling it out with unlimited budgets, Trans-Am took off in a way that nobody expected. From 1966 until 1972, it was the most competitive, most exciting race series in the world. Trans-Am made household names of Roger Penske and Mark Donohue, made fortunes for Carroll Shelby and Parnelli Jones, used up the fortune of Sam Posey and almost destroyed the reputation of Dan Gurney. There never was and never will be anything as gloriously crazy as the Golden Years of Trans-Am.

In the May, 1969 issue of Car and Driver there was a headline “Bishop Resigns in SCCA Shakeup.”

Depending on who’s telling the story, either Bill France from NASCAR called Bishop or Bishop called Bill France. Anyway, NASCAR put up most of the money to start a new company, with the rest owned by John and Peg Bishop. It was grandly called International Motor Sports Association, though at the beginning it was just John and Peg, along with their old friend Charlie Rainville.

John served as IMSA President, while Peg managed Staff, Registration, Timing & Scoring and pretty much everything else from their Westport, Connecticut offices. Charlie Rainville, a retired racer and SCCA Race Steward, became IMSA’s irreplaceable Trackside Director of Racing until his death in 1985.

It was already obvious in 1969 that racing Trans-Am sedans was a better idea than Can-Am or Formula 5000, from almost everyone’s point of view. IMSA adopted FIA Grand Touring rules, Group 4 for production-based sports cars and Group 2 for sedans, plus a “Baby Grand” class somewhere between Showroom Stock and Under-2.5 Trans-Am.

John quickly got FIA approval for his new organization, which meant the SCCA could not bar SCCA racers from also racing with IMSA. The Bishops also got RJ Reynolds as a series sponsor, an association that lasted for two decades with their Camel cigarette brand.

John Bishop deliberately patterned IMSA after NASCAR. The single innovation that made IMSA successful and John Bishop something of a genius was to pay Start Money as well as Prize Money. This meant that at the end of the day, when everyone was tired and thirsty and wondering how they were going to afford four new fenders and rebuild the top end, John and Peg Bishop would hand out checks. John and Peg Bishop turned road racing from a hobby into a business, and made everybody a professional racing driver. At tax time, you could write off all your racing expenses, because racing was your business whether you were General Motors or just the kid down the block working on his race car in the driveway.

By 1972, IMSA had taken on much of the upscale feel it would have throughout the next two decades. Bishop expanded with the RS series for Baby Grand “stock cars,” which was sort of Showroom Stock Sedans on steroids, lucrative enough that you could actually make a living racing a cheap little sedan.

Camel GT was even better. There were Corvettes and Trans-Am Camaros with 700 hp all-aluminum 454 big-block V-8s battling Porsche 911s and 914/6s. Bishop juggled the weights to make sure everybody’s performance was about equal. These disparate cars raced in long endurance races that required co-drivers, attracted more spectators and got more press coverage which attracted more sponsors.

In a very real sense, IMSA Camel GT made Peter Gregg, and Peter Gregg made IMSA. During the first eight seasons of IMSA, Peter Perfect won twice as many races as either Al Holbert or Hurley Haywood, who each won twice as many as anybody else. Peter Gregg’s IMSA performances probably convinced more people to buy a Porsche than even Steve McQueen’s 1971 movie Le Mans.

By 1974, through sheer ineptitude, the SCCA had pretty much destroyed Can-Am, Formula 5000 and Trans-Am. John Bishop took the opportunity to invent All-American GT, which led to wild competitions between Peter Gregg’s Porsche 935 Turbos and V-8 hot-rods like the Greenwood Corvette, DeKon Monza and Charlie Kemp’s Mustang II.

In 1976, the Bishops paid off Bill France and took complete possession of IMSA. The next year, John and Peg introduced American Challenge, which two years later became Kelly American Challenge with sponsorship from Kelly Services and a special points fund for women drivers. Stars like Lyn St. James, Patty Moise, Kathy Rude and Deborah Gregg began their racing careers thanks to John and Peg Bishop and Kelly American.

Starting from scratch, within a few years, IMSA was the best-known, best-regarded road racing organization in the United States.

In 1981, IMSA started Grand Touring Prototype, which was Bishop’s name for FIA Group C sports-racers. One car put GTP on the map, a Lola T-600 owned by Roy Woods and Ralph Kent Cooke, driven by Brian Redman to five Firsts and five Seconds out of ten races to win the 1981 GTP Championship.

As the Reagan economy took off in the Eighties, so did IMSA GTP, with Jaguar, BMW and Porsche challenging Lola. Porsche’s 962 came to dominate GTP as thoroughly as Porsche’s 917 had dominated Can-Am. The high point of GTP was 1988.

John Bishop had bypass heart surgery in 1987, then sold IMSA right at the top in 1989. The buyers were Mike Cone and Jeff Parker, who already owned the IMSA Grand Prix of St. Petersburg. They sold it shortly thereafter to Charles Slater, who in turn sold it to Roberto Muller and Andy Evans who changed the name to Professional Sports Car Racing. Don Panoz bought it in 2001, changed the name back to IMSA and made it part of Panoz Motorsports. Finally, in 2012 NASCAR bought IMSA and aligned IMSA, ACO and FIA regulations.

By then, John and Peg Bishop were long retired to an aviation country club in San Rafael, California. John was also one of the founders and Chairman of the International Motor Racing Research Center at Watkins Glen. John was voted into the Motorsports Hall of Fame, both John and Peg are obviously in the IMSA Hall of Fame.