Event Program: 2025 Sebring SpeedTour

How the Air Force Saved Sebring

Two Legendary Air Force Officers Saved The SCCA

By Rich Taylor

Modern American road racing began on October 2, 1948, when Cornell law student Cameron Argetsinger organized the first race sanctioned by the newly-formed SCCA, on the surrounding country roads and through the downtown streets of Watkins Glen, NY. During the next four years, the SCCA also famously sanctioned races through the streets of other small towns, including Bridgehampton, Elkhart Lake and Pebble Beach.

“Round the Houses” sports car road racing came to a crashing end on September 20, 1952. On the second lap of the annual Watkins Glen Grand Prix, Fred Wacker in an Allard J2 was leading Briggs Cunningham, John Fitch and Phil Walters in Cunningham team C-4Rs.

Cunningham passed for the lead as the quartet raced down Franklin Street. Wacker swung wide to avoid Briggs, but bounced his Allard off the outside curb. As he charged after the Cunningham, Wacker left behind a dozen injured spectators and a dead seven-year-old boy, Frankie Fazzary, who’d been sitting on the curb.

Within days, the New York State Legislature started working on a law to ban racing on public roads, and many other cities and states followed suit. It was immediately obvious that something had to be done. The clear solution was to race on smoothly-paved courses that could be closed off to safely separate spectators from the speeding cars, but creating a purpose-built road course took not only a lot of money, but a lot of time.

The instant answer was an airport…smoothly-paved and already designed to prevent pedestrians from wandering across the runways. Racing cars on airport runways and taxiways was nothing new. Back in 1936 and ’37, ARCA—the predecessor of the SCCA— had been involved with the revived Vanderbilt Cup Grand Prix races at Roosevelt Field on Long Island.

In 1950, Alec Ulmann had organized the first international race at what had been Hendricks Army Airfield, a B-17 training base in Sebring, FL. By 1952, there were already airport road races from Lyndhurst, NJ to Palm Springs, CA. In England, too, there were road races at many air bases, most notably Silverstone.

All these factors miraculously came together just a month after the fatal accident at Watkins Glen. On October 26, 1952, the Sports Car Club of America and U.S. Air Force Strategic Air Command signed an unprecedented two-year contract, breathtaking in its scope. Nothing like it had ever been tried before…or since, for that matter.

In return for contributions to the Airman’s Living Improvement Fund, the SCCA was allowed to organize weekend races on the runways and taxiways of Strategic Air Command bomber bases in California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nebraska, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Texas and Washington.

With the stroke of a pen, the SCCA went from a small group painstakingly organizing individual events whenever they could obtain a venue, to a nationwide sanctioning body holding road races all over the country at predetermined tracks at a fixed fee. It was a revolution!

How did this happen? Well, General Curtis Emerson LeMay was the founder of the Strategic Air Command and one of the most important American military leaders from World War II to Vietnam…and conveniently, a long-time racing enthusiast.

A graduate civil engineer from Ohio State, LeMay was commissioned a U.S. Army Air Corps Second Lieutenant in 1930, during the daredevil era of Billy Mitchell, Jimmy Doolittle and other pioneer military aviators. After flight training, LeMay flew as a Pursuit pilot before transferring to bombers in 1937.

He became a specialist in aerial navigation and precision bombing, and in 1941, was made commander of the 305th Bomb Group, flying B-17s from Chelveston Air Base in England. During World War II, he rapidly rose to command the 3rd Air Division, then the XX and XXI Bomber Command and as the war neared its end, now a Major General, LeMay was put in charge of all strategic air operations against Japan.

A month after VJ Day, Curtis LeMay personally piloted a B-29 non-stop from Japan to Chicago, setting a slew of aviation records. In 1947, he was made Commander of USAF Europe, which included setting up the 1948 Berlin Airlift. Later that year, he returned to America to head the Strategic Air Command, headquartered at Offutt Air Force Base outside Omaha, NE.

In 1951, he was made the youngest Four-Star General since U.S. Grant. By 1965, when his World War II assistant Robert McNamara—Lyndon Johnson’s Secretary of Defense—forced him into retirement, Curtis LeMay was Air Force Chief of Staff and the longest-serving Four-Star in American History.

Back in England, LeMay had become friends with an American pilot named Reade Tilley. After completing college at the University of Texas in 1939, Tilley planned to become a professional automobile racer. Instead, once Germany invaded Poland, he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force and was sent to England as part of American-staffed RAF Eagle Squadron 121, which became U.S. Army Air Force 335th Fighter Squadron in 1942.

Among other heroic exploits, Tilley volunteered to fly a land-based Spitfire from the deck of the American aircraft carrier Wasp in order to defend the island of Malta. On a second mission, he flew another Spitfire from the deck of the British carrier Eagle. During the Battle for Malta, Tilley became an Ace with seven confirmed kills and was awarded an RAF Distinguished Flying Cross.

After the war, Colonel Tilley was one of the creators of the Air Force Information Office, as Director of Information for Air Forces in Europe. He then came to Strategic Air Command in 1950 as Special Assistant to General LeMay. Now remember, Colonel Tilley had started out as a racing driver. One of the first things he did on returning to America was begin racing his Jaguar XK-120M with SCCA.

While in England, racing enthusiasts Tilley and LeMay had befriended Sydney Allard, a similarly larger-than-life character. A long-time racer and London Ford dealer, Allard had contracts to repair Ford-based military vehicles for the British and American military. In addition, his Allard race cars dominated international sports car racing from roughly 1946 through 1954, thanks to their powerful American Cadillac and Chrysler V-8s in lightweight aluminum-bodied British two-seaters.

In the Spring of 1953, General LeMay arranged for his friend Sydney Allard to test new JR race cars on U.S. Air Force bases in England, and in June, along with Cadillac engineer Frank Burrell, General Curtis LeMay, General Frank Griswold, Colonel David Schilling and Colonel Reade Tilley attended the Le Mans 24 Hours as guests of Sydney Allard.

They all got to drive the new Allard JR race cars on the Le Mans roads before the race, and when one of the Cadillac engines blew in Practice, LeMay arranged to have a new engine flown from Detroit to France in an Air Force military transport!

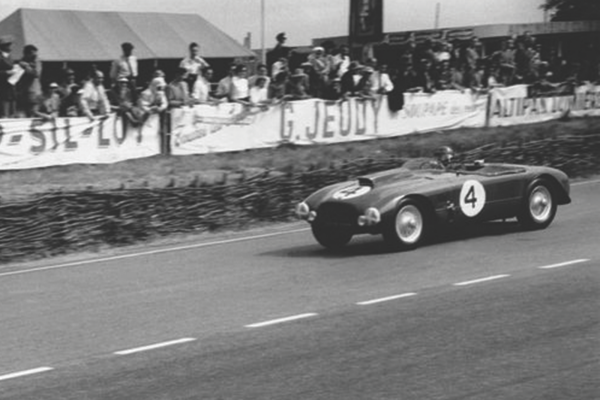

The rarest of all Allard models, there were only seven JRs built with special aerodynamic bodywork. Allard JR 3402, racing at Le Mans as #4, driven by Philip Fotheringham-Parker and Sydney Allard, lasted just 4 laps before a rear suspension arm broke and cut the brake lines.

After the race, General Frank Griswold, who had won the first Watkins Glen race in 1948 with his prewar Alfa Romeo 8C2900, passed on a chance to buy one of the JRs, choosing instead to have a K3 custom-made with a larger cockpit. So Colonel Shilling bought JR 3402.

General LeMay bought brand-new Allard JR 3404 that had been entered at Le Mans as #71 in case the team needed a spare, but was not actually raced.

Colonel Tilley bought Allard JR 3403, raced at Le Mans as #5, that Zora Arkus-Duntov and Ray Merrick shared for 65 laps until another Cadillac engine blew. Years before, Duntov had been Allard’s factory racer, but he now worked for General Motors in Detroit. He literally went AWOL in order to drive again at LeMans, and saved his job at GM only by claiming that he was doing research on racing Cadillac V-8s and improving the handling of the Corvette!

Once delivered to Nebraska, the three Allard JRs formed the SAC Racing Team, with Chief Mechanic Fritz Jacques and drivers David Schilling, Reade Tilley, Roy Scott and Fred Wacker, who was not only the wealthy owner of AAMCO machine tools, but the Allard racer who’d whacked the curb at Watkins Glen in 1952, killed Frankie Fazzary and as President of the SCCA, signed the contract with SAC!

Ironically, car owner Curtis LeMay was never listed as a driver on the SAC Racing Team. LeMay’s boss, Air Force Chief of Staff Hoyt Vanderberg, refused permission for LeMay to race. Vanderberg’s logic was similar to that of Hollywood movie studios who tried to prevent stars like Steve McQueen or Paul Newman from racing…they were too valuable to risk!

Officially, General LeMay had to be content testing his Allard in Practice and Qualifying. Unofficially, knowing LeMay’s tough personality, I wouldn’t be surprised if he didn’t anonymously show up behind the wheel of his JR during an occasional SCCA race, but I can’t prove that!

David Schilling crashed JR 3402 and was killed. JR 3403 and JR 3404 were raced until they became uncompetitive, and were eventually sold around 1960. All three cars have been restored; 3402 is currently in an American collection, 3403 in Germany, 3404 in England.

The two-year SAC/SCCA contract was not renewed in October, 1954, probably because new Air Force Chief of Staff Nathan Twining did not authorize it. In two years, however, SCCA had paid $335,000 into the Airman’s Living Improvement Fund, which most critics credit with helping keep qualified Air Force pilots, mechanics and crewmembers from leaving the service for more lucrative jobs in the private sector.

As thanks for literally saving the SCCA in its time of crisis, General Curtis LeMay was awarded the 1954 Woolf Barnato Award, the SCCA’s highest honor, and in 2007, 17 years after he died, posthumously inducted into the SCCA Hall of Fame.

Colonel Reade Tilley road raced for years, until he shipped overseas as Director of Information Pacific Air Force during the Vietnam conflict. He died in 2001. His RAF Flight Jacket and Mae West Life Preserver from World War II are displayed in the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Field near Dayton, OH.