Event Program: 2024 Indy SpeedTour

First Race at Indy

The Greatest Spectacle in Racing had been held on Memorial Day Weekend ever since 1911 except for 2020 and the war years when it was cancelled. What even most die-hard Indy fans don’t know is that the first car race at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway was actually held in mid-August, 1909.

Before World War I, Detroit was not yet established as the center of the nascent auto industry. Many manufacturers and suppliers were clustered around Indianapolis. Carl Fisher, co-owner of acetylene headlamp supplier Prest-O-Lite, decided Indianapolis should have a combination race track/test track, similar to the 2.75 mile banked oval that H.F. Locke King opened in 1907 at the Brooklands Estate in Weybridge, Surrey.

Fisher and three Indianapolis business friends—Arthur Newby of National Motors, Frank Wheeler of Wheeler-Schebler Carburetor and James Allison, Fisher’s partner in Prest-O-Lite—chipped in to buy a 320 acre farm on 16th Street, 5 miles northwest of downtown Indianapolis. In February, 1909, their construction crews went to work.

Armed primarily with hand tools, the workers carved a track with four identical constant-radius corners banked at 9 degrees 12 minutes, each one-quarter mile long. The corners joined together two five-eighth mile straights and two one-eighth mile straights, creating a symmetrical 2.5-mile oval that fit within a rectangle 1.0 mile by 0.5 mile. The track surface was 50 feet wide on the straights, 60 feet wide on the corners, paved in a mix of tar and crushed stone.

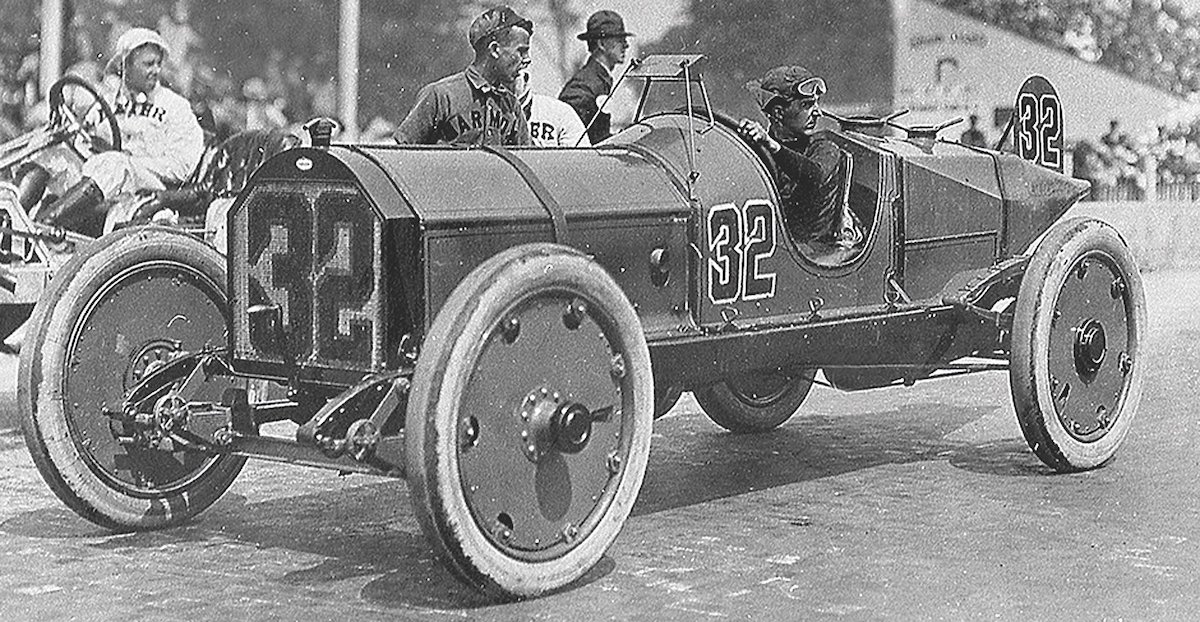

After a hot-air balloon race in June and motorcycle races in July before the track was even finished, the first automobile race was held on Thursday, August 19, 1909. Bob Burman driving a Buick won the first auto race at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, 250 miles for the Prest-O-Lite Trophy.

Tragically, during the race, Carl Fisher’s new track surface literally melted. Knox driver Will Bourque and his riding mechanic Harry Holcomb fatally crashed. Saturday, mechanic Claude Kellum and two spectators were killed when Charlie Merz crashed his National in the final 300 mile race of the weekend.

This was a major turning point in American motorsports. Carl Fisher and his partners had already spent a fortune on a race track in the middle of nowhere, with literally nothing to show for it except a potholed strip of oily gravel, five dead bodies and a lot of bad publicity. A normal guy would have walked away. Characteristically, Fisher dug in his heels and rushed to have the track repaved.

Reinforced concrete as used at Brooklands was considered, but quickly rejected as too expensive and too prone to winter frost damage. Brick was the most durable substitute available in 1909, so Fisher bought 3.2-million bricks and had his long-suffering crew repave the whole track. Starting on September 20, they hand-laid each 10 lb. brick, and got the whole job done in an amazing two months.

The moment the last brick was wedged in place, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway became the most sophisticated racing facility in America. Fisher had planned to add a road course that wandered through the infield, but now he and his partners simply couldn’t afford it. No matter. The newly-paved 2.5-mile banked oval, forever christened “The Brickyard,” was ready by December 17, 1909, when Lewis Strang won an exhibition race driving a 200 hp Fiat.

In 1910, Fisher organized three-day race meetings over Memorial Day Weekend, Fourth of July Weekend and Labor Day Weekend. In 1911, he decided that all these separate little races were a lot of work, a lot of wear and tear on his new track facilities and loss leaders, besides. Instead, he decided to hold just one race each year, but that race would be the richest, most important automotive contest in the world. Thus is immortality born.

Including contingency money, the purse for the single 500 mile race on Memorial Day, 1911 was $27,500. Winner Ray Harroun took home $14,250. By comparison, the highest paid baseball star in the country, Ty Cobb, made $9000 for the entire 1911 season. A skilled union machinist in Fisher’s Indianapolis headlight factory was paid $17.50 for a 50 hour week.

In 1912, Fisher increased the Indy 500 winner’s share to a nice round $20,000 out of a stupendous purse of $52,225. This made the Indianapolis 500 the highest paying sporting event in the world. The rich purse and resulting media attention meant that the race took on a life of its own.

In 1913, Carl Fisher and Jim Allison sold Prest-O-Lite for a fortune, just before electric headlights made their acetylene lamps obsolete. Fisher then conceived, developed and promoted the Lincoln Highway from New York to San Francisco, then the Dixie Highway from Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan to Miami.

He then made another, much larger fortune developing Miami Beach, then another developing Montauk, Long Island. In 2020 dollars, he was the equivalent of a multi-billionaire when he lost everything in the Crash of 1929. Now broke, his last project was the 1938 Caribbean Club on Key Largo, financed by friends.

Back in Indianapolis, when racing resumed in 1919 after a two-year hiatus during World War I, many American racers and engineers already thought of the AAA season as merely a warm-up for Indy. Some drivers became “Indy Experts,” skipping the rest of the season to concentrate solely on the Indianapolis 500. This meant that serious American race teams now headquartered year-round in Indianapolis or in the suburb of Speedway, Indiana that sprang up around the track.

Car builders quickly learned that their latest technological innovations would get the most attention if introduced at the Indy 500. Passenger car manufacturers learned that having their name painted on the side of the winning car was worth millions in free publicity. Drivers realized that a reputation could be made in one afternoon—“No matter what else you ever do, you’ll always be introduced as ‘Winner of the Indianapolis 500!’”